Rami Airola: This is weird. The way I remember it as that instead of Sarah having a vision of the necklace, she remembers seeing Bob. When half of the series aired again in 1995 (they stopped the series in episode 14), I think I remember seeing the necklace-vision for the first time. I wonder if they showed us the European pilot, but then again I don't remember seeing the "Mike shoots Bob" scene until I many many many years later bought the VHS of the European pilot that was released in Finland separately. Maybe they showed the European version, but cut before the last half hour.

chalfont: I can't really remember my initial reaction to the pilot other than everyone really liked it. I remember my neighbours had taped it on VHS, so we watched it a few times.

Gabriel: I found it fascinating and utterly unlike

Dallas. It was downright spooky yet very funny and very sad. My grandparents gave up at episode 3, but my parents and I stuck with it. My grandparents had rented a TV and VHS machine (as people did back then) so they let me have their old Betamax machine. I used all their old tapes to record the show. There was just enough room to fit George C Scott's

A Christmas Carol on the end of one tape as well. My grandparents are gone now, so there's going to be a bittersweet feeling relinking with the show after so many years. So many family members gone, friends moved on, me having moved cities twice…

Ross: I still vividly remember watching the pilot. My dad was watching something else on the main TV, so I ended up watching alone in our basement. My mom watched on a portable black & white TV in the kitchen. From the start of the opening credits, I was mesmerized. The visuals with Badalamenti’s music had me hooked. I kept thinking, what is this great music? To this day I’ve never seen a more perfect pilot episode. Everything in it set up the show perfectly. Most TV series have OK pilots and then they end up finding themselves and getting better.

TP was unique in that everything clicked in that first two hours. I was instantly hooked. I remember my mom was really affected by the scene of Sarah on the phone. Again, so unlike anything seen on TV before. After that, I taped every episode, and those tapes got watched countless times over the years. I was thankfully able to tape the pilot episode when they repeated it in the summer.

I got both of my brothers to start watching it after that. But as far as I remember, there wasn’t much talk from other kids at school about the show, in fact that first year the only other people I knew that were watching it were my two brothers and my mom. But I remember the media hype starting. There was an article in the

USA Today newspaper about the show’s popularity and the “viewing parties” that were going on. I was surprised, and excited, that it was getting so much acclaim and attention. I think people tend to think that ratings were huge the first season, but they weren’t. The pilot’s ratings were, but the remainder of the season did just so so. Many thought it was too weird, or off-putting. But the media hype and “cool factor” kept it in the mainstream. But there was a lot of talk that it may not get renewed for a second season. It was far from a sure bet.

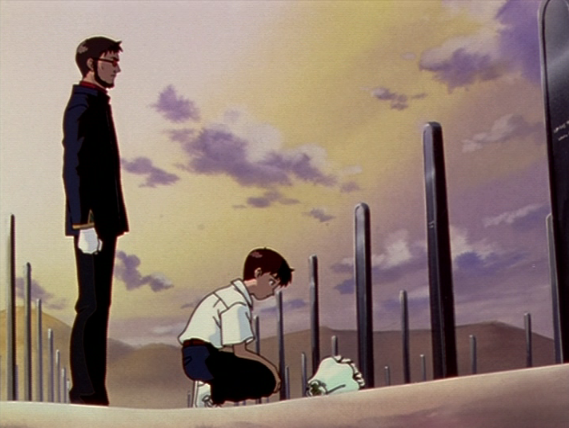

2. The appearance of Bob in episode 1

Rami Airola: Again, I recall I saw this in the pilot the first time I saw the series. I was horrified by the sudden image. In episode 1, it was also scary to see Laura's face suddenly appearing over Donna's face. There was something very frightening in it.

Audrey Horne: Creepy, but didn't give it much thought. I know enough to know that is a big red herring.

Gabriel: Didn't exactly see him as 'BOB.' Sarah Palmer was freaky and weird anyway and this bloke Lynch was an oddball, so why wouldn't she see (what I thought was) a 'Red Indian' (different era, different ways to describe people) at the end of the sofa? I thought perhaps he was a native spirit who might be a good guy.

hopesfall: I remember [my sister] constantly telling me that Bob was a ghost, and the scene where Sarah screams at the vision of him when Donna's face changes gave me nightmares for literally weeks.

HoodedMatt: There was a raised eyebrow. I think I said something like "is that the killer? No it can't be. Is she remembering?"

Ygdrasel: Scared the hell out of me and intrigued me.

Ross: Honestly, I don’t remember exactly what I thought at that point, but I loved the bizarre, mysterious, and even horror under-pinnings. As to who that was, I don’t think I had any guess.

BOB1: Strange enough, I don't remember any reaction! But I do remember that by the time Episode 4 had its premiere, when Andy is drawing a portrait from Sarah's vision, the shadow of BOB was deep within me…

3. The Red Room dream in episode 2

Audrey Horne 9 (including the rest of episode 2): Okay, this show is great. Again, thank god I recorded and kept these. Already watched the pilot and second episode at least five times, have made friends watch them. Have a notebook with notes. This episode is amazing, there's a whorehouse?! Cooper throwing rocks?! The spooky rich girl is doing another dance?! Ha, Lucy sticking her tongue out at the new FBI jerk! Love her the most. ...wait, what the hell is this dream?! Episode over, mind blown! This show just jumped to another level. Rewatch the dream again and again. Tons of notes in my pad. Hurry up next week!

Gabriel: The papers had mentioned a backwards-talking dwarf. I'd assumed it would be some crazy person showing up in the RR. The sequence was really odd and yet funny. I wasn't sure where it would lead. A lot of it was simply strange words and myth-building that wouldn't make sense until later on.

Rami Airola: I was already horrified by the weird shaking this weird person was doing. And when he turned around, looked very weird and sounded even more weird, I was absolutely terrified, but also very interested in it. I had already a habit of watching horror movies. I was both terrified and fascinated about all kinds of scary stories. I think I was even somewhat traumatized by the scene, as for years and years I saw nightmares about the midget and very often when I closed my eyes I was too scared to open them again because I was afraid that the midget would suddenly be right in front of my face, looking and sounding all weird! :D Even though I was so young, I always knew that movies are just movies, and they are not real, but at nights the mind goes to weird places. And besides, Michael J. Anderson wasn't acting his weird appearance because that was all him. That was how he really looked like, so in theory it could've been possible that he would've had appeared in my room some night, and man that thought was scary as hell.

Ross: I remember this pretty vividly as well. I remember turning off the TV after the episode ended, and just thinking, Wow! Definitely the oddest, weirdest thing I had ever seen. But so fascinating. I think when some people go back and revisit the show they are surprised at how early that came in the run of the show. And it definitely got people talking. They might have lost some viewers, but gained more. Even if a lot of people were saying WTF, it sure had them talking. Personally, I loved the idea that it was some kind of code. And the sequence with Bob/Mike was scary, and since I have always been a horror fan, I loved those aspects of the show. It was also really cool seeing Laura.

BOB1: The dream itself made me something like "oh! how cool!" without giving it any deeper thought. However Cooper's revelation of "I know who killed..." was a real shock. And then a week later it was so WHAAAAAT?! to see that he simply doesn't remember :D

Ygrdasel: My only visual exposure to

Twin Peaks, prior to watching, was a still shot from the Red Room. When the scene came up, my attention was glued. Loved every aspect of it and loved everything involving it after.

HoodedMatt: Being told that there is a dwarf who talks backwards and experiencing it are two entirely different things. I was not prepared for the beautiful absurdity that is the dream sequence.

The rest of Season 1

Audrey Horne: I love this show! On

Donahue, the other guy who's not Lynch says it's coming back next Fall, yay! Laura's not dead, right? The cousin is... I saw

Vertigo, I know! By now, after Audrey muscled Batis and cried while watching Leland, and smoked in the closet I am fully on the "Audrey Horne and Agent Cooper best characters ever on TV" train.

N. Needleman: I watched the show live on ABC with my mom when I was about 8 or 9, and then returned to it as a young teen when it was running on Bravo. My mother brought me in around Episode 2 or 3 and made it clear she thought Leland was the killer. She did not elaborate much as to why, but she said "his reaction was too much" re: Laura's death. I was afraid of Leo and was fascinated by Dr. Jacoby and his glasses.

4a. The season finale - the fact that Laura's killer was not revealed

Ross: I wasn’t mad at all about the killer not being revealed. But I WAS surprised. I honestly thought he would be. Not sure exactly where that expectation came from, but it was there. And a lot of people were pissed. It was really the first turning point against the show.

HoodedMatt: It didn't bother me at all that Laura's killer wasn't revealed. I'd become so caught up in all the various plots, and the fact that they all seemed to be playing into the main one at this point, that it didn't matter.

BOB1: I think it was becoming more and more obvious that the deeper we sink into the mystery, the more mysterious it gets ;) So I probably didn't expect revealing the killer.

chalfont: Don't think I expected that the killer would be revealed.

Gabriel: Never expected him/her to be.

Ygrdrasel: I never expected the killer to be revealed so it wasn't an issue. I got super hyped by all the cliffhangers though.

Audrey Horne: The killer is so obviously a "good guy" ...the Sheriff or Donna. Maybe the father. Guys quit complaining about not finding out who the killer is, the show has so much more going for it!! Okay, Nadine and Leo are dead, right? Those characters have outlasted their usefulness. Ha, love Catherine telling the sweet but dumb waitress to shut up she has a thing in her mouth. Those two will be fine. Go, Catherine, you're fantastic! Ohhhhh, my god, Audrey! How are you going to get out of this one?! Ahhhh, yes, she left a note for Cooper...

4b. The season finale - Cooper being shot.

Audrey Horne: Wait, no Cooper, noooo! Okay, no way he's dead. No way. Truman or Donna shot him. I'm fine with not knowing and spending months thinking what is going to happen. This is the best show ever!

Ross: There was a bit on the finale on some entertainment show (most likely

ET?) where they were showing people’s negative reactions to the ending. I loved all the cliffhangers, and was pretty convinced that at least some of the characters would die.

chalfont: Oh no!!!!

BOB1: Cooper being shot was a blast and let us (a group of fans at school) develop a range of theories including Coop's twin brother and such stuff!

Gabriel: Someone had been watching

Dallas! To be honest, it actually was a little too Grand Guignol for me. There were enough cliffhangers without one where the main character (obviously) wouldn't die. I was more concerned about Audrey, James, Shelly, Catherine and so on.

Rami Airola: Didn't do much for me. I guess I knew that the hero wasn't going to die. Also, I didn't think of it as a season finale as I recall the series just continued the next week.

HoodedMatt: I flip flopped over who shot Cooper a lot, mainly between Leland (he was wearing a black coat too) and Ben.

Ygdrasel: This was the big "I gotta see what happens" cliffhanger for me. The payoff was ultimately disappointing though. My memory's fuzzy but wasn't it basically "Josie shot Cooper because no real reason at all"?

The summer between seasons

Ross: I can’t remember the exact date, but I know the cassette(!) single of the "Twin Peaks Theme" and Julee Cruise’s "Falling" came out sometime before summer (and before the full soundtrack). People on here know how much I love the music of

TP, and know my blog. So this first release was very special and I used to listen to the tape on a continuous loop.

That summer I prepared to leave for college in the fall. I hoped my brother would be able to tape all the episodes for me while I was away. I was relieved that the series was renewed, but worried about its move to the Saturday “death slot”. There was a lot of talk about that in the media over the summer. With ABC touting it as a new “must see” night. I watched the reruns of the first season that summer (even though I had them taped). I bought the

Twin Peaks soundtrack on CD (the first CD I ever bought), and bought the

Diary.

Audrey Horne: Best summer ever. Late September. Got me the

Rolling Stone! Kyle is dating Donna Hayward? Lame. Madchen portion cool, great photo! Donna, zzzzzz. Audrey pic!! Of course she's a virgin. Thanks

Rolling Stone, great article! Newsweek just told us Bob did it?! Bob, that's not even a main character!

Time magazine!! Four new photos from the second season! Cooper on the floor with blood, he'll be okay. Audrey in the OEJ [One Eyed Jacks] outfit, is she hiding behind a tree escaping in the woods, awesome! Josie and Ben with wine glasses... Oh, this is going to be good. A Giant? Kyle hosting

SNL. Best skit ever! Lynch going apeshit on Kyle for nonchalantly spoiling that Shelly the waitress killed Laura Palmer. MTV music awards... Sherilyn and Ontkean!! Emmys yay! Wait, Fenn is sick and not there, boo! Wait, Kyle lost, boo! Whattttt,

Twin Peaks lost? Boooooo!

5. The Secret Diary of Laura Palmer - did you read it before watching season 2? Did it point you in a certain direction?

BOB1: Yes.

No. (But I never guess anything in any crime story)

I read it with unbelievable excitement.

Even more unbelievable, I still read it with equal excitement!

chalfont: No, I read it a couple of years after the show.

Ygdrasel: I bought the

Diary and have yet to read it, actually. Same for the

Access Guide.

rocketsan22: I read every

Twin Peaks book I could get my hands on as I caught the bug badly. Heck, I even blew off a visit to the White House during a class trip to Washington as I was so engrossed in Cooper's book…

HoodedMatt: I didn't read the diary until after I'd seen the series and the movie, so I probably didn't get as attatched to it as I may have done. While I do love it as a piece of writing and think it is invaluble as an artifact detailing Laura's mental state during her ordeal, I have to say that I find some of the events don't really work for me in regard to the series. I really can't imagine either Donna (Moira Kelly or LFB) doing the whole skinny dipping thing as it's written in the book, and the whole business with Leo and Bobby doesn't really ring true to me for some reason. I think it was probably more useful to Sheryl Lee than it is essential for fans of the show & movie.

Ross: Even though the first season had ended by pissing off viewers, and it was moving to Saturdays, there was still a good buzz going into the second season, Lynch was on

Time, the soundtrack was a hit, etc. I know I read the diary in those first few weeks away at school, and really wondered how Bob was going to fit into the show. I wondered how the killer could just be some guy that wasn’t one of the main characters.

USA Today had a full page article on the second season premiere, and if I remember correctly, pretty much said Laura was killed by the “dream demon” Bob of the diary. And at that point I had no inkling that Bob would actually be “possessing” one of our main characters. Maybe others had that figured out, but I don’t think I had. Back to the diary, I remember really liking it, but for as many times as I’ve rewatched the series and

FWWM over the years, I never went back and read the diary. Not entirely sure why. I think for me

TP was so much about the visual and aural aspects, that the printed story doesn’t do as much for me.

Rami Airola: Loaned it from the library after the series had ended. I remember we were at the library with our class. I was either still on the second grade or then I was on third. Can't really remember. Anyways, kids at school knew about

Twin Peaks and people knew I liked it. So when we were at the library, a girl in my class came to me and said she found a

Twin Peaks book. I got very excited and loaned it immediately. I read it through very quickly. I was a good reader. I learned to read when I was 4 years old. I guess it was pretty much my first PORN book also :D It had pretty damn raunchy stuff for a kid. I remember also that later at school we all had to draw a picture of some situation in the book we loaned. I draw Bob singing the Matilda song. My teacher commented that I perhaps shouldn't be reading a book like that.

Audrey Horne: People said it came out before the second season premiere. For some reason, I bought it after the second episode, so maybe I waited a week or two. Strange since I was obsessed. So for me it was after we already had a lot of Bob and the Giant. Read it for clues. I didn't care about Laura as a person, only as a plot device. Still thought man, this girl has a lot of time on her hands to do all these things, how does she micromanage? I can barely do my math homework. Okay, the killer is Ben, Leland. I don't think it's Donna anymore. Hmmm, Ben seems kinda obvious but I guess it ties into the stars of the show with Audrey and Cooper, so that could work going forward. Leland? That would be creepy.

Gabriel: Read it in the UK break between seasons over Christmas. Fell in love with Laura Palmer. Always will be a bit in love with the character. She wasn't much older than me and I had difficulties of my own in life, particularly at school. I started to see a different world existed beyond those gates. I had wondered if Harold Smith was a code name for Harry S Truman. I assumed the JH mentioned on her list of 'partners' at the orgies was Jerry Horne. Certainly, there was a hugely dark, sinister underbelly to the town, not unlike the sex cult in

Eyes Wide Shut, painted by the diary that was never really exploited in the show or the movie. And obviously the diary gave real focus to BOB.

N. Needleman: I was also devouring all the ancillary material I could find, and I remember walking into a bookstore to read Laura's

Secret Diary - it's inconceivable today that that was actually a promotional tie-in book for a major network primetime series that anyone could read, but I did (and did not tell my mother). I was very young and even skimming it its content freaked me out, so I put it down and didn't look at it again for years. I could tell someone had abused Laura Palmer but I didn't know who, even though I was already wary of Leland - Ray Wise's performance had always kind of freaked me out, but I just never made the connection until the reveal. Between the episodes airing and the book I had a sense that the show was much more enchanting and interesting with these strange new things, but also was becoming much more adult and scary. And I was right.

6a. The season 2 premiere - the very long opening with the waiter

Audrey Horne: Um, after school job, I'm not feeling well I have to stay home tonight... Suckers! Okay, okay, okay, long credits, get to Cooper, and get to Audrey! Hey I remember this little old guy from

The Searchers, fun! Okay, okay enough, enough... I can't take it anymore!

rocketsan22: I was hooked from the moment I heard the theme song and saw the visuals of the saw blades... I was riveted by the writing and the drawn out interaction with Cooper and Senor Droolcup.

Ygdrasel: I found this very strange. Is the waiter just crazy senile? Surely he sees there's a shot man. I enjoyed the strangeness though.

chalfont: Remember that one well. Seemed liked it lasted the entire episode!!!! Was really frustrating!!!!!

Gabriel: Arty, interesting to look at, but frustratingly paced. It had some awesome moments, but the draggy pace might well have put off some fans. Lynch seemed to be delighting in annoying the viewer, but that's not always helpful.

HoodedMatt: I loved it. Pure genius. It still makes me grin when we rewatch the episode. The juxtaposition between the bleeding to death Cooper and the semi-oblivious Senor Drool-Cup is just brilliant.

Ross: I remember the scene doing exactly what it was meant to do- make you feel antsy and anxious. It certainly didn’t make me mad or anything, and I appreciate it even more over the years. However, this is where the backlash really kicked into high gear. There was a review at the time that stated that during these scenes with the waiter “you could just hear the collective TVs of America turning the channel.”

6b. The season 2 premiere - the appearance of the giant (which certainly takes the vaguely supernatural air of the show in a new direction)

Ross: I loved the supernatural slant, in fact it's definitely part of the reason I prefer eps 9-16 even more than season 1. But it certainly added to others tuning out. I think it may have also added to the feeling that many people had that the show was going nowhere, and that Lynch & Frost were just making it all up and throwing in things that were just weird for weirdness sake. Another really strange thing was that during the original broadcast (at least in Chicago) of the Giant’s “clues”, all of his dialogue was dropped out. I think it was some sort of glitch- but my brother was convinced Lynch did it on purpose to fuck with people. I didn’t hear the scene properly until perhaps the Bravo reruns?

BOB1: Myself - I loved the waiter and giant from the first sight. But I went to school, started asking friends and... a look of

![Rolling Eyes :roll:]()

unfortunately. Good thing I was just ending that school and soon after holidays I'd meet a pack of new friend who appreciated the supernatural

Twin Peaks more than anything in the world!

Gabriel: Having read the diary, the supernatural element wasn't unexpected. But the Giant was. Had no idea what to make of him, but he seemed like a good guy. It's interesting that he wasn't part of the Lodge Gang in

FWWM. I wondered after the series ended whether he was a White Lodge spirit, hence he only showed up in the waiting room.

N. Needleman: The introduction of more spirits to the show like the Giant did not really faze me as a kid - I think it was just instinctual for a child to assume that of course there are more "ghosts" in such a weird and wonderful place and story.

HoodedMatt: I think I did an actual double take. I wasn't sure where the sequence with the waiter was going, but I didn't expect it to go there!

rocketsan22: I didn't know what to think but I knew it was fantastic…

Rami Airola: Freaked me out.

Ygdrasel: Loved it. The Giant was in that still shot I'd already seen so his appearance was kind of an "OH MY GOD, IT'S THAT GUY!" moment XD His last line to Coop was brilliant too.

Audrey Horne: Finally, that giant. Cool, more clues... I will write them down later but let's get to One Eyed Jacks, please!

The rest of the season 2 premiere

Audrey Horne: There seemed to be a lot of long scenes in the middle at the hospital, and not as strong as the pilot, but hey it's a TV show and it's going to be a full season, no problem. Ouch, that Donna scene with James. Is Maddy finally going to reveal she is Laura? I love Pete. Yes, Albert is back! No Catherine, she's the shows best actor! Yes, finally back to OEJs. Glorious brilliant Audrey... Uh oh, she's in trouble. Awkward Hayward dinner, poor Leland. Audrey praying to Cooper... These two are magic together.

trevanian: [Rosenfield's] reaction to Ed shooting Nadine's eye out is still the biggest laugh in the whole series for me.

Ross: People often complain that

TP suffered from Lynch’s absence from the series, but ironically, the turning point against the show really started with this LYNCH directed episode. (And of course Lynch was away for a lot of season one). Personally, I love the episode, and think the 2nd season premiere is certainly one of the most important episodes of the series. It sort of “resets” everything in so many interesting ways.

One more point to make is that I remember people complaining about the new still-frame “Next On” segments for season two. Saying that were another case of the show being enigmatic while showing nothing.

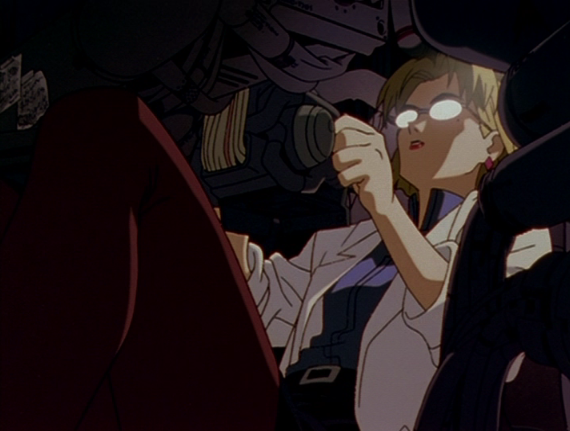

6c. The season 2 premiere - the violent flashback to Laura's murder, with Bob making his first sustained appearance

Ross: God I loved this scene. Still the scariest scene in

TP. I remember the weird theories. There was the guy who was convinced Bob was giving Laura CPR!!! And others that thought Laura was turning into a vampire!!! (Her back teeth during her scream look a little like fangs – especially in standard def).

rocketsan22: I was scared sh!tless...I didn't know what to think. My mind was racing and I longed to fill in the pieces I had missed…

Gabriel: Great. Also, subsequently, a different view of the death scene from

FWWM.

Audrey Horne: Ronnette waking up, what the hell is this? Good lord, that is horrifying. So that Bob thing really did do it. But who is he? Leland, Ben or Truman. I think Donna was out of it for me by then.

BOB1: What I find very strange is that I don't remember any first reaction to the ending of Ep.8 at all. I think I was so preoccupied with the Giant and his prophecies that the graphic and explicit images of BOB somehow were too graphic and explicit. I'd rather see BOB but not the body ;)

Ygdrasel: I don't recall Bob appearing but the murder did seem very brutal from the flashbacks.

Rami Airola: I think I was covering my face with my hands at that point.

chalfont: Very scary!!!!

HoodedMatt: I was surprised at how far they went with the sequence given the time it was made. Seeing Bob for as long as we do was creepy as heck, too.

N. Needleman: I was terrified of BOB and would flee the scene any time he appeared, especially for Ronette Pulaski's nightmare at the close of that episode. I also was keenly aware of the weird stillness and pauses David Lynch kept adding, and they always frightened me.

7. Bob crawling over the couch in episode 9

HoodedMatt: It made my skin crawl the first time. There's a hunger in his eyes that, coupled with his primal movement, just chills the blood. Sheryl Lee's reaction as Maddy put the icing on the cake, too.

rocketsan22: One of the most memorable moments on the show…

Ross: Amazing.

Ygrasel: "Oh shit oh shit oh shit!"

Rami Airola: The absolutely most horrifying scene ever. After that I saw many many nightmares about Bob for years.

Gabriel: Terrifying. Utterly cool. I loved the show for being so funny and yet so scary. I felt like my concepts of what could be done on TV were being blown wide open. It was becoming difficult to watch much other TV in light of

TP's iconoclasm.

chalfont: The most frightening moment in TV history. Need to say more??

Audrey Horne (including the rest of episode 9): Crying, crying hard. Had to work Saturday night at family restaurant. Got home by 10:30 to discover my mother had changed the channel and my precious VHS tape was now recording NBC's

Carol Burnett and Friends! Frantically change channels to hear Truman tell Cooper, "Audrey Horne is missing." Noooooooooo! The television gods are cruel. Still plenty of stuff though to come... Audrey with Batis, hell yes! Leo in coma, sexy scene with Bobby and Shelly in the car, nice. What the hell is this? James, Donna and Maddy (the holy trinity of lameness) singing? Um, okay.... Wait, wait, wait... God, that is scary as hell. Okay, this Bob guy really is getting to me. More scary dream from Cooper, more Bob, owls, phone call... Audrey in the red drapes! Yes, yes, yes... Oh no. (Surely Cooper knows where she is now, right? And the killer is Ben or Leland.)

The buildup to the killer's reveal

Audrey Horne: Not even thinking too much about the killer because I think we are not going to find that out until the end of the season. Friends make me go to

The Rocky Horror Picture Show on the night of the OEJs raid and all the commercials for that week show Cooper threatening Nancy. First memory of

Rocky Horror Show is only God, I can't wait to get home and watch this in the middle of the night!! Three in the morning jumping up and down when Truman, Cooper and Audrey escape! (Those three together are going to run shit on this show!). What, they ARE going to reveal the killer in two weeks? Okay. Oh and by the way, Catherine is totally that Japanese man, right? Ahhh, Cooper and Audrey reunited and it feels so good. Cooper and nemesis Ben Horne, perfect. Oh, Cooper's old partner is crazy and on the loose. Okay,

Peaks, we get the foreshadowing about the ex partner and Audrey. Gee, wonder who he will threaten? That should be good. Jean Renault, great villain too... Should get plenty of mileage out of him now that Leo is useless. Do we really need all these new characters? Harold, Dick (he's the worst), and back off Syd (Cooper is Audrey's). Well, surely they won't introduce more unnecessary players in this already perfect ensemble.

trevanian: Pretty much every Miguel Ferrer moment is a rewatcher - I used to leave the tape with the 'I love you Sheriff Truman' line cued up, I so love that bit.

N. Needleman: My memories are pretty sketchy after [watching the premiere and reading

The Secret Diary]. I can tell you I was very frightened of Harold clawing his face a few episodes later and the way Maddy screamed.

Rami Airola: Well, the scene where we find out that Tojamura is Catherine freaked me out. It was such a shock to suddenly hear a woman's voice from a man's mouth! :D

Ross: [The killer's reveal was] the highlight of the series for me. A lot of people had jumped ship already by this time. The biggest argument people have today about the show is that it solved the Laura mystery too soon. Some of this has to do with the fact that Lynch didn’t want to. But the biggest complaint at the time was that it WASN’T giving people that answer. And a lot of people had given up on it. So prolonging it would never have helped the show back then. To me, it feels like a natural progression. And it gives us a sensational payoff. One of the most amazing things about

TP is that after all the buildup, one might be afraid that any resolution would end up being a letdown, when in fact they managed to elevate the show to new heights.

Audrey Horne on all of episode 14: The reveal! Ohh, boy. This is it! And I'm watching alone. My cousin (Laura, natch) is calling me and also getting in on the last minute action. So this is the episode where Cooper is going to bring them all together and tells us and them how and who did it! Honestly, as long as it's not Audrey, I will be fine. And we can finally move on to other mysteries in this great town. Hmmm, this is really good, but we are running out of time if Cooper is going to solve this. Okay, it can't be Ben. Yes, Glorious Audrey, twist the screws to your father and give Cooper that info! And Pete and Catherine reunited, and yes it does feel so good. Thank god, Catherine is back! Oh, Christ Donna and James, shut up! Oh wait this scene is really, really good. I love this Julee Cruise music. How is Cooper going to solve this? Sarah, are you dead?! Ugh, shut up Maddy you pointless character. Wait, Leland. Oh, my god, the mirror! Ahhhhhhh. No, no, no, Maddy, you are not a pointless character! Run! Run!!! Get out of there!! Speechless. What am I watching? Crying. Stunned silence. Can't wait for next week. Completely forgot Cooper didn't solve murder. This is too good. Next week Cooper tells Audrey to lock her door! Oh my god this is going to be good. Can't wait for the rest of this season.... Can only get better!

![]()

8a. The killer's reveal in episode 14 - the fact that it was Leland

Ross: As for the Leland thing, I honestly can’t remember if I was surprised or not. I don’t think that I was really ever trying to guess the killer back then, just going along for the ride. And in the end Leland made the most sense.

Rami Airola: I recall I knew it already. It might be that people in general knew it already. Maybe it was spoiled in the magazines or something way too early.

Ygdrasel: I was spoiled on this but also found it a suitable twist as I wouldn't have expected it otherwise. It was a great reveal.

rocketsan22: I was at a dinner party which I only agreed to go to if they would let me watch

Twin Peaks at 9pm... I can't say I was surprised, Leland was off the rails at that point.

HoodedMatt: I had an inkling that it might be him after he killed Jacques and the way he switched from high emotion to stone coldness when he heard someone coming, but seeing that confirmed the way it is in the episode was almost traumatic.

BOB1: [in response to the entire scene] SHOCK SHOCK SHOCK

![Shocked :shock:]()

![Shocked :shock:]()

![Shocked :shock:]()

MORE SHOCK SHOCK SHOCK etc. I'm pretty sure I stopped breathing when Leland was standing in front of that mirror

![Shocked :shock:]() Gabriel:

Gabriel: My parents had friends over. I watched the show on my own in my bedroom on a 14-inch TV. I recorded it so my parents could see it right after. I knew the killer would be revealed. When I walked into the lounge after the episode, my Mum asked if I was all right. That I looked disappointed.

In myself perhaps . . .

I was psyched for the episode. I knew the killer would be revealed. I kept thinking: 'Cooper will figure it out.' At the Roadhouse: 'The Giant's going to help Cooper!'

The atmosphere as the record scratches on the turntable. Stifling . . . like a house with all the doors shut and the central heating turned too high for too many hours.

I wanted to know who the killer was. Why isn't Cooper figuring it out? It's Leland! Oh God! As if the sordid tales of abuse in the diary weren't terrible enough, it's her dad and he raped and killed his own child!

8b. The killer's reveal in episode 14 - the fact that it was also Bob

chalfont: Somehow, I think I knew a couple of weeks before….

Ygdrasel: I already knew that. Why were they investigating him all this time otherwise? Clear supernatural origin, it wasn't a shock that Bob was involved in the murder.

Rami Airola: I had taped the episode on VHS, and I watched it the morning I had to go to school. My parents were gone and I was alone. The sudden appearance of Bob and his terrifying laugh scared me greatly. I remember being afraid to be alone at home after that, so I went to school so early that no-one else was there yet. Even though it scared me, I was hugely fascinated by it.

Ross: The duality with Bob was ingenious.

rocketsan22: I loved this aspect...that it was likely done out of Leland's control…

That was an interesting twist that part of me had been expecting since the flashback, but I wasn't sure exactly how they'd play it. To be honest, I'm still not certain if the show portrays it as a pure possession or not, despite that being Ray Wise's view point. I like the ambiguity.

8c. The killer's reveal in episode 14 - Maddy's murder (maybe the most disturbing thing I've seen in a TV show or even movie)

HoodedMatt: Totally heartbreaking.

N. Needleman: I fled and hid under a table in Episode 14 when the final sequence started with the record player skipping - I just listened to it from down the hall, which may have been worse, honestly. Maddy was my favorite character at the time so it was all pretty rough. I remember the Louis Armstrong bit early in the episode and I didn't know who the killer was, but the goodbye scene with Leland and Sarah had me ill at ease and I had a sinking feeling Maddy wasn't going anywhere. My dazed mom had to recap it all.

HoodedMatt: I'd grown to like Maddy a lot and to see Leland & Bob imperfectly recreating their murder of Laura was frightening. Again, I was shocked at just how much they got away with in that sequence. Like the flashback (or, as I take it, Ronnette's imperfect memory) of Laura's murder, they really pushed the envelope. About halfway through it I realised that they had had to shoot the whole thing twice, with Leland and Bob killing Maddy, and my level of respect for Sheryl Lee went up so much.

rocketsan22: The dinner party people were confused as hell...I loved it...and couldn't fathom how I was going to get through the next week.

trevanian: Just drove me up the wall. I had really been expecting a very traditional melodramatic resolution; in fact, ever since seeing the falls outside the hotel, I thought Cooper and BOB would probably tangle and go off the falls together a la Holmes' original death with Moriarty. Also when it did start up, I thought Leland would throw off the mantle of BOB before killing her. So I was practically kicking the TV set in as it went down. My longtime girlfriend and I were in the final stages, but had been watching the show together up till that point, and she didn't come home in time from an outing to watch that episode, so I was very angry about that too.

Rami Airola: I remember explaining to my friend what I had just seen on

Twin Peaks. We were together at the toilet room and I showed how Maddy was cornered and how Bob was showing the "come on" gesture with his hands. For some reason that detail was totally terrifying, and I still find it one of the best little details in the series. It makes Bob even more menacing.

Ross: Still amazed that Maddy’s murder made it through the censors.

Ygdrasel: Her murder was very disturbing. It was that scene that made the "Bob's possessing him" stuff click.

Gabriel: I wanted to know the secret, but not like that. Cooper doesn't rescue Maddy. She gets beaten to death in front of me. I hadn't seen

Blue Velvet at that stage, but it was a Jeffrey hiding in the wardrobe moment. I'd confronted the good guys losing in TV shows down the years, notably

Blake's Seven, but not to see Cooper burst through the Palmers' front door, Truman and Hawk in tow . . .

. . . the good guys failed, the town's epic mystery was a domestic tragedy and I'd sat there as a voyeur and watched a young woman beaten to death in order to sate my appetite for an answer to a mystery.

As a teenager, all this hit me on an emotional and psychological level I'd never really experienced. I felt shaken and just . . . different. The series had a darker hue, closer to the diary at that point. The show actually grew up (or maybe I did) with that episode, but it could never quite manage the quirky joie de vivre it had before without seeming superficial. Wonderful television.

Audrey Horne on episode 15: Okay, nice follow up to the reveal of the murderer. Leland is nuts! Ray is crushing it! More new characters? No, not now, guys. Now that Ben is not the killer, I can bask in the brilliance of the Horne Brothers. Okay this is a filler episode, but that Cooper/Audrey scene was pretty good... Where are her saddle shoes?! Maddy in plastic, genius. What, two weeks for the next episode?! That is bullshit!

Thanks,

Entertainment Weekly, for showing a picture of Leland freaking out in a interrogation room with blood on his head, and for saying the next episode will have wake! You suck.

9. The way the discovery & capture of Leland/Bob is handled in episode 16

Audrey Horne: Who's directing this? A little heavy handed guys. It's okay, it's okay. Get to the Audrey scene. What, there isn't one? Yes, Cooper is gathering people at the Roadhouse! Have all my notes on how the murder was done, Cooper is so smart! ....ummmmmm, almost a year for that? All those clues and brilliant writing for that?! Laura whispers the killer in his ear?! Cooper, you are the worst detective ever! And thanks for coming, Bobby, Hank, Leo, Ben, Major. You can go home now. Ray, beautiful work dying. You will be missed. Not sure about juxtaposing Dick, Andy and Lucy with it. Um, is that a computer generated owl in a junk yard? Please don't do that again,

Twin Peaks. It doesn't suit you.

BOB1: Here I'd love to disagree with both the honourable creator of this thread and the honourable main contributor to this thread :) Ep.16 was for me from the first time - pure perfection. And the roadhouse scene - brilliant. The interrogation scene - mesmerizing. Leland's confession and Cooper's speech with water sprinkling and Laura Palmer's Theme playing - best ever.

Rami Airola: At this point, every single thing that was dealing with Bob was hyper fascinating to me. I remember thinking that if a person with Bob inside him touches water, it makes Bob leave. :D

Ross: For years this was my favorite episode. I still like it quite a lot, but I’d put the Lynch episodes ahead of it. I understand the complaints that it wraps up things too quick though.

Ygdrasel: The discovery seemed nonsensical. They just gather and suddenly the Giant decides to quit holding out info. The execution of the capture was wonderful.

HoodedMatt: I'm torn on this. On the one hand, I find it too on the nose and corny - the bit with the waiter, Leland and the gum is possibly the worst moment of that sequence for me - but at the same time it does kind of work. I do wish they had waited until the end of the season before capturing Leland, though. I would have liked to have seen Leland/Bob and Windom Earle taxing Coop, Harry and the gang and working at cross purposes for a time.

Gabriel: Too easy. The characters make their minds up that they'll catch the killer, so they just catch him.

It's as if, had they had that determination in the pilot, they'd have caught him right away. Leland's capture doesn't feel earned anymore. Beautiful, emotional death scene though and the storm feels as if it's lifted.

rocketsan22: This episode made me a fan of Ray Wise. This episode...and the scene a few back when he admits to killing Jacques Renault...are riveting to watch. It was the pain Ray Wise was able to make me believe that kept me transfixed on the show throughout its run.

10. Leland's wake in episode 17, with the comic subplots emerging and the writers trying to move past the mystery

HoodedMatt: Worst idea in the show. Sarah gets brushed off, nobody reacts to the reveal and it feels almost like another show altogether.

BOB1: How EMBARASSING!! How can

Twin Peaks be so stupid. My family who had been watching me and my growing fascination for the past weeks now must be looking at me and secretly mocking me... that twin peaks of his is sort of dumb, ain't it?... Oooh.

Ross: I think the thing that disappointed me the most was the fast forward of the three days. I understand it though- they wanted to move past it. But there are things I would have loved to see. How did Sarah react? What exactly did Ronette see? Just Bob as in her vision? Or Leland in real life & Bob in her vision? Or Bob AND Leland?? And most of all, I did feel a bit cheated that we didn’t get to see Donna react to the news. After all, pretty much every scene with her in the series up until then was her trying to figure out who killed Laura and then to find out it was Laura’s own dad, whom she had just had that harrowing & bizarre interaction with…

But I actually still love the series post-Laura. Actually, my complaint with the second half of the series has always been about what we DIDN’T see rather that what was there, most of which I still like quite a bit. Lynch complains that the Laura story was forced out. But just because they solved the murder didn’t mean it had to end. They could have kept Sarah in the story. Had Donna visit Ronette. Etc. Better leading to the Black Lodge story.

Rami Airola: I just remember Sarah talking about a man with dirty grey hair. That alone got me pumped enough to watch this and following episodes.

rocketsan22: Thought the whole episode felt rushed. Still do…

Gabriel: Massive fail. The comedy feels false after the emotional tone of the last few episodes. Cooper needed to return to Seattle for a while. Laura's death and the revelations about Leland should have led to shockwaves across the community. The 'Eyes Wide Shut' cult from the diary should have started mopping up people who knew Laura in the event worse things in the town get exposed.

Audrey Horne: My friends the next day.... " it's all fluff!" Me... " shut up!" But seriously though, what happened? Remember the town in the pilot that grieved when the homecoming queen died? Well, another pillar of the community died violently. Do they think they are attending a wake/funeral of a father that raped and murdered his child?! La la la good potato salad. Or were they informed no, no it was a supernatural spirit that jumped into his body? And in that case, it's still la la la good potato salad. Corkscrew!!!! Good lord, that is worse than the computer owl in the last episode. Not to worry, Audrey and Cooper will take us out of this mess. Or kinda. Cooper sets up the rest of the season for the Audrey/Cooper/Crazy Partner Plot and rebuffs Audrey. Basically, see you for May/end of the season Sweeps, Audrey. Time to give the other actors a plot for the off winter months. I've watched

Cheers and

Moonlighting, I know how the romantic leads work on this "will they or won't they" machine. Ah, and Cooper is out of the FBI... Perfect way to keep him in town. Okay, a couple of lackluster episodes but it will be fine. After all, they have to do a whole season this time.

Ygdrasel: I enjoyed the plots at the time. Mostly. There wasn't much payoff though. Still wholeheartedly love everything Dale/Briggs/Windom related.

11. The realization that the Cooper-Audrey storyline was not going to play out

Audrey Horne: Never realized it until much, much, much too late. They were prominent for September and November. Network sweeps time. Burn off James, Nadine, Norma and Ed in the TV lull months. Wait, Audrey's falling for Bobby? Aha, not so fast, she's only doing that to get info to save Cooper. Glorious Audrey! She knows what she wants and isn't going to give it up for anyone other than Cooper. Hmmm, why is she helping her father, don't let them make up, that's no fun. Where are the saddle shoes, man! February sweeps mostly Josie? James?! Okay, okay that's done. Windom Earle playing with cards of production photos from

Twin Peaks?! That's just lazy now! Aha! Windom has selected Audrey as the target, and planted the mask of old First flame Audrey in Cooper's bed! Nice recall of when she put the OEJs mask on too. Finally we are back on track! Wait, Shelly and Donna also get notes from Earle? Um, okay but that seems like a lot of red herrings, we know he's going after Audrey because of Cooper, right? Huh, why are they introducing another fake out guy for Audrey? We already have the crazy ex partner plot. Is she falling for him? Fine, whatever... We need conflict. But it seems it's been awhile since we've had a Coop/Audrey scene. And that guy in the cowboy suit is probably bad news anyway.

Ygdrasel: Agitation and anger. Pure and simple. "Who's Annie? Audrey's hotter."

HoodedMatt: Disappointed. They should have stayed friends and then grown to become more as the series went on. Probably by series three or four. Alas, it wasn't to be.

Gabriel: It just fizzled out without me really noticing. I suddenly realised the characters had hardly any scenes together. A shame. Cooper's old nemesis is after Audrey and he hardly blinks. Odd.

BOB1: It was quite unimportant for me at that time.

Rami Airola: Didn't much care about this subplot at that age.

rocketsan22: I was glad Cooper stuck to his morals.

Ross: Of all the questions and complaints about the show, this is the one I least identify with. Don’t get me wrong- I love Audrey, and there was crazy good chemistry between them. But I never ONCE thought they would actually go through with a romance where Cooper reciprocated and actually had sex with a high school student. It just never entered my mind as something they would do, or something that I wanted to happen. So I was pretty surprised to learn years later that that was actually what was planned! And that so many fans actually wanted that to happen.

For me, I just don’t believe Cooper would betray his inner code of conduct like that. Almost any other character I would believe. But not Cooper. I would have been all for them continuing the flirtation as it was, but that wasn’t the plan, and that’s not what Kyle objected to (or claimed to object to depending on whose side of the story you believe). I think it's important to remember that.

I will say, though, that one of the bigger mistakes the show made was dropping their interaction once they decided a romance wouldn’t happen. I would have liked their friendship & mentoring to continue, and maybe see Audrey’s reaction to Annie. But their reduced interaction didn’t seem unnatural at the time, as Cooper’s investigation was over and Audrey was dealing with her dad.

12. The stretch of episodes 17-23 (you know the ones)

Ygdrasel: I don't know the ones offhand, actually. My "The show's gone downhill" moment held off until the episodes that decided James needed to travel and we had to be there with him.

Gabriel: A waste of time. At the time they seemed less bad because I couldn't see the story in overview. So I stuck with it. The hope was that it would pick up after a lull. The James/Evelyn plotline seemed like a reject from a Zalman King film of the era.

HoodedMatt: I'm not as down on them as many people seem to be, but they are the worst episodes of the show. There are some diamonds in the rough, but they are mostly moments rather than stories. I do love how Andy and Dick become awkward friends over the Little Nicky thing, even if the kid himself is a little irritating (and the thought bubble is facepalm material). The least said about Evelyn Marsh, the better.

Rami Airola: Waited for Bob or some other terrifying stuff to appear. It was ok. The only subplot I really didn't care about at all was all the mill stuff with Catherine.

rocketsan22: I'm currently watching them again for the umpteenth time. Struggling to get through them. I always fast forward through the Civil War crap, it's too much to take. There must be something that drew me back in originally because...man is this stretch of episodes...bad…

Ross: See my answer for number 10. But I still do like quite a lot of what IS actually in these episodes. One point to make here is that since there was no internet back then, I lived with only my own ideas and opinions for most of the years. Even when

Wrapped In Plastic came along, their (mostly positive) opinions on these episodes were close to mine. It wasn’t until much much later that I found out how much disdain there was for these. I was actually quite surprised to learn [about it]. I never even hated the Evelyn story. Granted, it's slight, but it's still done with style and some really great music.

I do remember my one brother asking where the series was going during these episodes though, and he didn’t return to watch it when it later returned from hiatus.

In some bizarre way, the more unfocused feel of these episodes makes sense, as in life after getting the answer to something you were so focused on.

Highlights for me include:

-Ben & his home movies

-The tape “Hobgoblins” message from Earle (one of the best written & delivered speeches in the whole run)

-Michael Parks

-The whole ending of ep 20: Dead Dog Farm, Leo, the vagrant’s body.

-Earle’s intro

I was really bummed when I read in the

USA Today that the series was going on hiatus.

BOB1: Now like I wrote above, I went to a new school and was lucky to meet a bunch of Twin Freaks. And that was at the time of that "stretch", say starting around Ep.19 which was definitely after the beginning of the schoolyear. So for me it was no stretch - every episode we would record, rewatch, rediscuss... on and on and on... perhaps that is why I still like those episodes :D

And then BOB's reappearance on Josie's death bed made me crazy with excitement as pointless as it actually is ;) I even have a proof written: at this time I was writing a diary for my mom who was away for 2 months. It says something like: "and now the most important news of the week: BOB is back, hooray!", he he.

Audrey Horne: Hmmm, no one is watching this with me anymore. No one saw last night's episode? I'm only rewatching an episode maybe once or twice. Little Nicky? C'mon! Did you really just put another bad special effect in this show? Was that a thought bubble on Andy's head?! Huh, Lana is the most captivating woman in this world? Have you guys paid attention to the press over the past year? You know you have Fenn, Amick, Chen, Lee on this show, right? This Evelyn Marsh plot is really, really, really dumb... And I'm a stupid teenager. This white lodge, black lodge stuff is hokey. Knock it off. Really, Jean Renault? You're going to let a waitress in and get taken in by her shapely leg? Remember when it was months since the last time we saw Mike Nelson? Well he's back, yet Audrey is only getting that one scene in Ben's office?! Yes, Thomas Eckhardt and Andrew Packard, this should be good. Oh, never mind. What ever happened to One Eyed Jacks? Josie shot Cooper because he came here? Dick Tremayne, you should be on another show, pal. What the hell ever happened to Sylvia Horne? Oh there's Johnny. Thank god Leo is out of that coma. This should get good. Never mind. It that another special effect with Cooper's First Audrey as a thought bubble? Wait is that Evelyn Marsh? Fuzzy VHS tape! Evelyn was Caroline?! Nadine and Mike are the highlight? Nadine kicking Hank's ass, fun! Peggy Lipton is the most patient person ever... Has she been allowed one decent plot line yet?! Even her bad review and mom from hell came as an almost tag on scene. Okay, okay, now that Ben is back, Earle got the note to Audrey, and Cooper solved who shot him we can move on to the fun!

...what the hell? hiatus?! Josie in a doorknob?! This show better come back!

13. Where you felt the show picking up again

Ross: For me the show always fell distinctly into four parts: Season 1, Episodes 8-16, Episodes 17-23, and Episodes 24-29. I really love the last six episodes, and enjoy them just about as much as any other span of episodes. I feel like most of the characters are at their most appealing here. I think Welsh is fantastic, and I think everything ramps up towards the conclusion. And then there’s Annie. I fell in love with that character just as quickly as Cooper did. To me, she was exactly the kind of person I would see him with. Kind, gentle, guarded and yet open, wounded and yet happy. Everything worked for me, and every scene they are in together is a series highlight for me.

trevanian: I think the show started winning me back even during the worst run of shows, because I was absolutely fascinated by the whole lodge idea (Frost's version of it, anyway - Lynch's is visually appealing but not intellectually satisfying, not that he is going to lose any sleep over that complaint from me), and I knew I was going to hang in till the end just to see how that played out (though the end of the series was nearly 'Maddy dies' in the level of feeling infuriated.)

For me, the joys associated with Annie and Heisenberg really elevate the final batch.

Ygdrasel: It's been a while so I can't say where things 'picked up' again. Maybe when James and Donna stopped being a focus.

Rami Airola: Didn't think about things like that at that age.

rocketsan22: Windom Earle for sure…

HoodedMatt: Not until the final three or four episodes. I'm an Annie fan and her whirlwind romance with Cooper warmed my heart - Annie's insecurities really spoke to my own and I loved how she seemed to lose them when she was around Coop - and I really like the stuff with Windom Earle in disguise and the Angels thing.

Gabriel: Towards the end, although I never really bought into the Windom Earle storyline as played out. Silly disguises, the cabin in the woods . . . he was a bit like a villain from the 1960s

Batman series. The bit with the white face, red eyes and black teeth was great though, but never picked up on again.

Twin Peaks had developed a reputation for doing something randomly odd/quirky/sinister, but it seemed only for the 'What the Hell?' of it, without real purpose. I still loved the show all the way through, but I loved it the way I love the second and third

Indiana Jones films. I love the Laura Palmer saga the way I love

Raiders of the Lost Ark.

Audrey Horne: Yes, yes, yes. The last six episodes are coming back! Please get it together because I want it to continue. Oh god, what will happen in a few years when I have to go off to college? I hope I have a VCR and a TV so I can continue recording. Recap by Cooper. Nice. Ugh, there's that guy with Audrey again. I did love him as a psycho in

Dead Calm, though. I'm sure he's a psycho in this too. Wait did they just show a clip of Cooper with some skank on a boat? Whatever. The episode is back and I am happy. ...45 mins later. What the hell was that?! Little pine weasel? Audrey locking lips with the psycho

Dead Calm guy? Did she say there's no one in regards to Cooper when

DC guy was crooning to her? Wait, another fake out love interest and now this one for Cooper?! Oh she was in that Cory Haim/Cory Feldman

License to Drive movie. And she died in the

Drugstore Cowboy movie. Well, she better do the same here and get off this show! Wait, hold the phone, Norma of the wasted plot line has a sister?! James Marshall, Joan Chen and Ray Wise are off the show. It's a little sad that it is changing and they are bringing in more lame characters. This chess plot is going nowhere. Yikes, Crazy Ex Partner's disguises are the worst! Hmmm, nice to see Dr. Jacoby again, wish he was still creepy. I guess they have nothing for Dana Ashbrook to do. Didn't he kill someone in the pilot? What happened to the Bookhouse Boys?

Oh good Christ, Ben is obviously Donna's father. Whip de doo! Lame. Hey, whatever happened to Audrey knowing Ben and Catherine were burning down the mill? Man, has it really been over three months since there's been an Audrey/Cooper scene? No matter they will have plenty coming up. Yes, Ben and Catherine together, more of this please. What is with that sweater/

Dead Calm guy? Yay, Cooper is back in the suit! What, what, what, what?! Diner, Cooper telling a joke to

License to Drive girl. Sweet music. Truman asking how long he's been in love with her?! I waited almost a year for that line to be used elsewhere and you guys are wasting it on this? Are those tears streaming down my face? Owl Cave, ah this should be good. ...never mind. Miss Twin Peaks contest is coming? Um, the

Twin Peaks of April 1990 would never stoop this low. Oh yay, the Crazy Ex Partner is now making giant papier mâché chess pieces and somehow going unnoticed lugging it up to gazebos with dead bodies inside. Again, the

Twin Peaks of 1990 would never stoop so low. What the hell is next, a zebra costume? ...wait, I spoke too soon.

Ahhhh, yes Cooper is having a nice fireside chat with

Dead Calm guy. As soon as he Cooper leaves, I'm sure

DC guy will meet up with

License to Drive Jennings Yoko Ono and reveal their dastardly plot. Why else would they be there? Ahhhh, remember being excited when I read in

Rolling Stone magazine that Audrey is a virgin and won't compromise. That should pay off beautifully later on. Um.... Again, never mind. But we do get the one bright spot... Audrey hanging out with Pete. Already these two have great friend chemistry and if only it had happened earlier. Oscar and Emmy and Golden Globe nominated Piper Laurie gets to wear bulky coats and fiddle with a box within a box within a box. Remember when she told Shelly to shut up, "I'm thinking." Donna, pass the peas, please!

Okay, I would like the ending to this with the red room finally coming back in that pond and Bob's scary hand, and oh shit was that the high school hallway?! But it is thwarted with Audrey deflowered by the wrong, wrong guy, Cooper kissing THAT GIRL, and the Giant warning him. I can only take solace in hoping that the Giant is warning him that the whole show and story has gone horribly, horribly wrong. Yay, Lucy's voice comes on at the end to tell us they are wrapping this up in June. Surely they can fix this mess. ...never mind. They are pulling the last two episodes and burning them off after May Sweeps. Ah, only a few short months ago I was looking forward to the end of the season with the Cooper/Earle/Audrey plot. So naive.

14. The finale (and I know it was a 2-parter in '90 but I'm particularly keen to hear how the Lynch half played)

N. Needleman: [The week after the killer's reveal] I tried to rally and come back, but during a commercial break in

China Beach, which my mother loved, they showed some promo which had that clip from Episode 14 with BOB laughing in the mirror like an animatronic puppet. That's still incredibly scary to me, and when I saw that I ran to my bedroom and stayed there for most of the remainder of Season 2. ;) I saw episodes here and there, bits and pieces but it's mostly impressions. My poor mother then was faced with the task of explaining the series finale to me, which was a real narrative, I can tell you. I think she thought the Red Room was "a carnival tent." She was very precise on the details though.

chalfont: I was home alone (my childhood home was a house in the woods....) and was too scared to watch it live at night. (I saw the opening credits, and there I saw Ray Wise was on on the list and that was it for me... :-D ) Had to tape it and watch it the next morning. Actually, I think I was home alone for the pilot too…

rocketsan22: Bittersweet as by this time I had a very deep connection to the show, and before this, only

Star Wars had ever captivated me enough to invest emotionally in fictional characters. In writing this today, I liken my appreciation to

Twin Peaks to the same reason that

Lord Of The Flies or the writings of W.P. Kinsella hold true to me to this day...wonderful characters woven together with the most beautiful scenery.

Audrey Horne: Okay, it has been about a month and a half.

Peaks has become a punching bag for critics, an afterthought for most viewers... Is that still on? Long gone is the glory of doughnuts, dancing dwarfs, saddle shoes, the cherry twist, Angelo's music on the radio. I have only one friend that will even come over and watch this as... shudder, the Monday movie of the week. If you knew what they put on for the other Monday Movie of the Week, you'll know just how low this has fallen. Yet, I am still clinging. Maybe we will be surprised. Dugpas, Jupiter and Saturn meet... What the hell are they talking about? Annie and Shelly mention Laura Palmer to Norma. Was she from the same show? Nice try, guys. In the funniest unintentional moment, deflowered Audrey tells her father she hopes, "it doesn't hurt this much in a week." The hilarity of Miss Twin Peaks practice. I turn to my friend and actually apologize. Then the real kicker, Annie (I can say her name now since it's been a few months) and Cooper talk about trees and planting in their underwear. Seeing Cooper in action and using his subtle metaphors, I rethink the past year. Maybe it was better that Audrey got out of this mess. But then the piece de resistance! Brilliant Crazy Ex Partner guy truly destroys anything left holy and pure from the pilot in his Log Lady costume. If the billowing smoke from a log cabin, the untended owl cave, the papier mâché body weren't enough for the law enforcement, this is the end all be all for Cooper is the Worst Detective Ever! I can only turn to my friend and pat them on the knee and apologize again. We also threw popcorn at the Annie/Cooper bedding scene.

Waitaminute! Another hour? And it's directed by Lynch?! Good luck, David. You'll have your work cut out for you and this shitstorm.

Hmmm, Andy and Lucy in a sweet, simple scene. That was good. Hmmm, the tone is different. Cooper in the Sheriff's office. Hmmm, that was good, that was dark and interesting. Ronnette! Hey this is getting pretty good. I sit up, the music is working, the mood is changing... Could

Peaks be back?!

BOB1: one of the most exciting moments of my life. For the record: in Poland Ep.28 was screened normally, a week earlier, and then there was this last week... hell, the TV programme says it's gonna be just 45 minutes. How is it possible to end such a plotline in 45 minutes? And then... directed by David Lynch... my heart's going up my throat, the pulse is getting wild, yes! it's gonna be SOMETHING, I know it. And then... under the sycamore trees....

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA!!!!! This! It is THIS. This floor, these curtains, this little man. It felt whole and it was.

Rami Airola: Taped it on VHS and watched many many times. After this I was a

Twin Peaks and David Lynch fan for life. I was into horror, but nothing else really was quite like that.

Ygdrasel: The finale was brilliance.

HoodedMatt: The true return to form for the show. Lynch brought the quality right back up to season one heights and I loved all the little call backs he did and was so happy to see Sarah Palmer again after so long away. The ending left me stunned. A real jaw-dropper of a moment. I love just how much Kyle commits to the "how's Annie?" moment.

Gabriel: It wasn't a two parter in the UK (not that I remember!). The first half of the episode is stylistically back in season two, episode one territory: dragging out scenes to annoy the viewer. The bit in the bank was particularly irritating for me that evening. The point of the episode seemed to me to be about Cooper. The fact that I knew it was the last episode and they were throwing in loads of cliffhangers with the characters made me nervous. I suddenly thought 'Don't be predictable and trap Cooper in the lodge or have BOB take over Cooper!'

So I loved the artistic, horror aspects of the episode, loathed the cliffhangers. To this day, I've never considered it 'The End.' It was an end-of-season cliffhanger that wasn't resolved. If Lynch does a bunch of cliffhangers at the end of the new season with no sign of resolving them, I swear I'll chuck my TV out the f***ing window and never watch any TV show again!!

Ross: I was so sad that TP was coming to an end. And going out with no fanfare (and another hiatus!) I still remember seeing the brief commercial for the finale (which isn’t on the blu ray).

I was impressed with it at the time, and my love for it only grew more over time. The first thing I noticed about it was the soundtrack. “Dark Mood Woods” was amazing and instantly created a mood unique to this episode. I loved that Cooper finally entered his dream world. I loved seeing Sarah, Ronette, Laura, Maddy & Leland again. I was pretty shocked by the ending. And was pretty upset that that might be the end.

As for the other stories, Norma/Big Ed & Nadine came full circle. I never thought Ben was dead. But I did think Audrey, Andrew & Pete were dead. I was very surprised about Audrey until I heard that she would have survived.

I remember watching the pilot again soon after and realizing the Bobby/Shelly/Heidi bit was repeated and thinking how cool that was.

At the time there was talk that another network, or even first run syndication might continue the series. But I don’t know if those avenues were even pursued. The backlash was so bad at the time that I don’t think anyone wanted to touch it. Fox had said they would have picked it up if it was cancelled after season one, but I guess they had no interest by this time. I remember the letters to

TV Guide about the finale were NOT kind.

Of course Lynch then decided to do a movie…

15. Fire Walk With Me

rocketsan22: By this point I would have taken ANYTHING new

Twin Peaks related. I must have seen the movie six or seven times in the theatre as it showed at one of the artsy theatres in Montreal where I was going to school. I'm pretty sure I snuck in a pocket tape recorder so that I could relive the story at home.

Ross: Since my love for

TP never wavered, I was excited beyond belief to see

FWWM. I was initially disappointed to hear it was a prequel. But there was the promise of more to come, and I hoped there were going to be hints of that in the film. There was so little written about it beforehand, with no internet. It wasn’t until close to it coming out that I learned LFB had been replaced. That really bummed me out, and I had no idea she, Kyle, & Fenn were all jumping on the anti-

Peaks bandwagon.

I saw it opening night while away at school (taking a summer class). It was actually pretty packed being a college town. The next weekend I saw it with my brother while back home. I think there were two other people in the whole theater(!). I did manage to see it a third time during its short run.

I actually loved the film from the beginning, and never really understood the criticism. In fact, the absolute hatred from critics was really disheartening at the time. I remember when I found the

Video Watchdog issue on the film, and finally saw there was SOMEONE else who loved it!

I was surprised to see so many characters left out- mostly because I had heard they WERE in the movie. I had read interviews/articles with Ontkean, Chen & others saying they had filmed scenes. So I kept waiting for them to appear. It wasn’t until later that I learned they had all been cut.

Other than that disappointment, my only complaints with

FWWM were always the cosmetic things. WHY did they use a different house? Why didn’t they throw a wig on Norma? Etc. Etc. I wanted it to visually match the series. But the movie itself I’ve always loved.

BOB1: I was flabbergasted and delighted and all, and I went to see it in the cinema once again (you can imagine that it was no hit so must have stayed on screens for a rather short time) - inviting for this experience the girl I was in love with all through high school. The situation between us was rather clear. She knew I loved her, she never pretended to share my feelings but we were good friends and spent quite a lot of time together. It was also clear that I am a huge

Peaks-fan even though it had been a long time since the show's end. She used to watch it, too, of course, but like a regular viewer, not a freak ;) Well anyway, I told her there was this

Twin Peaks feature film and I loved it so let's go and see. So we went. Well we never really got to talk about it too much. It seemed she was taken aback. I remember one thing she said right afterwards: wow, she said, that doesn't look like a film I wanna see ever again in my life. But it didn't have to mean "I hated it." I don't suppose I want to see

Trainspotting ever again and still I find it to be a masterpiece. I can very well understand that

FWWM can be so emotionally shocking and morally challenging that it is hardly bearable. Personally I did not have this problem. It's the film by Lynch that I've watched the most times I suppose :)

Gabriel: Saw it day one of its UK nationwide release. It's a terrific film and, for all it doesn't have a lot of the regular cast, it fits stylistically with the show up to the point where Maddy is killed. I was watching a lot of Lynch and other arthouse directors at the time thanks to Sky Movies and to UK video distributor Palace Pictures going bust, meaning a lot of VHSes were selling plentifully and cheaply. I loved the film and wanted more. The same addiction to the show I had up to the killer reveal returned. And I hoped for a long time that, in spite of a bunch of snobby French film critics and the Ciby 2000 fallout, that there would be more.

Rami Airola: It was shown on television in early 1995. I taped it and watched it through on a daily basis for quite a long time. I think that after a few years I had already seen it more than 30 times. Back then it was the best movie I had ever seen, and it still is.

hopesfall: It took me until way into my late teens before I got round to seeing

FWWM and reading Cooper's autopbiographical book. I loved the book but didn't like the film at all. I actually only started to appreciate the film years later, and now absolutely adore it and class it as one of my favourites of all time.

Ygdrasel: The very first viewing was done amid a general "This can't be as bad as Wikipedia said..." mindset and also much distraction and pausing. Due to said distraction and fragmented viewing, I was left with little coherent memory of events, general confusion at what I'd watched, but a deep intrigue and desire to see it again.

BlackMoonLilith: Fire Walk with Me is an interesting case. I loved it when I first saw it and love it now... but for very different reasons. When the show took that infamous mid-S2 turn, I was hanging on by my fingernails to the mythology as something to look forward to. I think Lynch's last episode fulfilled my hopes that it'd be a way to save the show, but even more than that, I thought the film was an absolutely satisfying and complete experience to someone who was interested in BOB/MIKE/Red Room and wanted answers. We often hear that Lynch's work "doesn't make any sense," but I completely disagree. His vision has such a unity to it that even though I may not able to use words to explain to you what exactly happened in Scene X or Scene Y, it DOES make sense on an emotional level. I think a lot of his critics even realize this, but then overthink it;

Eraserhead is a good example of a film that I think almost everyone "gets" in terms of what's Henry's going through, on romantic, parental, and existential levels, and then assume they didn't get the film because they don't have a rational explanation why the chickens twitched and squirted blood/vomit/goo.

All of which is to say that while I may not have known exactly what MIKE was talking about when he mentions a "formica table top," I got that this was a connection between him and the Little Man, even before he places his hand on Gerard's stump. I didn't know why the left arm went numb, but I knew that it linked Laura and Teresa's experiences and lives and their connection to both the supernatural and Leland. Once MIKE asked for the garmonbozia and the subtitles revealed their meaning, the whole context of BOB and MIKE and their role within the town suddenly makes sense: BOB horded Leland and Laura's grief and suffering, MIKE wedded him to the ring and gave Laura a chance to die, thus allowing the grief to be spread more evenly out across the town (as we see in the pilot). For the humans, it's incomprehensible cruelty and misery, but it's only currency or maybe even a drug to beings who don't have our morality. I thought this was a more than satisfactory conclusion to what was set up by Episode 2's dream as well as Frost's late S2 stuff. I felt like the mythology was wrapped up in a nice little bow, even if I couldn't tell you how Lynch tied the knot.

The funny part about it is I failed in terms of instinctively grasping the story Lynch actually wanted to tell. Laura's own story didn't really get me that much. LostInTheMovies has talked about how it wasn't until rewatches that he realized the power in 2x01's final scene and Maddy's death, but I can honestly say the film was that with me too. Perhaps it was the Deer Meadow section, perhaps it was watching it at work on a laptop with headphones, but I was distant from Laura. I have no idea how now, as everything after "Who knows where or when CLICK" is drowning in Laura's perspective, but it was still more of a "finale" to the mythology to me, than an exploration of sexual abuse. Along the same lines, it wasn't until I was discussing the film with a friend did I realize all the stuff that suggested Leland wasn't an innocent. I mean, it's clear as day now, but at the time, I had just taken Episode 16 on its word and viewed all the creepy dad and Teresa stuff as that evil spirit indulging in an innocent man's body. It took me the second or maybe even third rewatch to really get the film on this human level, which is weird cause I feel like more people connect with the human stuff and THEN the supernatural, but for me it was the other way around. I still love and am fascinated by not just the mythology of

TP in general, but the mythology of

FWWM which I think is some of Lynch's strongest "weird stuff," but I more prefer the film now as the broken life and eventual redemption of this endlessly fascinating character, given one of the two best performances from an actress I've ever seen in a film along with Megumi Ogata in

The End of Evangelion (another franchise that has me hooked on both the complicated mythos and the raw humanity).

But at the time, it was all "Of course! The Little Man is MIKE's arm! The Little Man IS MIKE!"

HoodedMatt: Loved it, in spite of and because of its darker tone. The Chet Desmond and Deer Meadow part was a little disconcerting at first, but I got into it as soon as they hit the airport and saw Lil. The FBI sequence was a surprise, in part because of David Bowie and in part because of the Convenience Store footage. By the time we hit Twin Peaks itself, naturally, I did miss some of the series characters who weren't there - Lucy & Andy the most - but it felt right that we stayed with Laura and her ordeal. The ending felt like it was the perfect way to end the story - not totally closed or tied up, but Laura was free from her torments and looked truly happy. I cried when she broke out into that beautiful smile in the Red Room while Cooper stood behind her.

Nightsea: I've gone back and forth over whether or not I should post this. I've been a visitor to these discussion boards for a while, but didn't join until recently. But one of the main reasons as to why I joined is to be able to respond to the

Fire Walk With Me aspect of this thread. There's no need for me to delve too far into this, nor would I, but I know what it's like to be abused at a young age. Essentially I knew nothing about