These are not necessarily the movies I consider "greatest;" they're closer to being personal favorites I would be most compelled to watch at a given moment. I've ordered them roughly by preference, though looking at the list it feels rather arbitrary...and of course, it could change in a minute or two. Links are to my reviews of the given film.

I just respond to the style here above all else - it's so restrained yet burning with intense energy. The movie is also a great example of the raw reality of documentary inflitrating a fictional story. And Jean-Pierre Leaud's internal monologue in the cinema is one of my favorite movie speeches ever.

Although it's legendary as spectacle, the power of the movie lies in its fusion of character with landscape - geography as psychology. A perverse and violent adventure epic.

Simultaneously raw and elegant, this is Hollywood's masterpiece. Though I've seen audiences laugh along with it, it's startling for me to see it as at all comic (though like all Hitches, it has a sense of humor). The tragic, dreamlike aura seems overpowering.

This is a spiritual film to its core, even (especially) while exposing the crimes of organized religion. We are with our protagonist, but Dreyer doesn't let her off the hook either, and the conclusion could be seen as a reverse-miracle version of

: the dark side of having enough faith.

A shattered and shattering family portrait, with a moment that still gives me goosebumps: Michael Corleone embracing his brother while staring coldly in the distance, with ominous intensity. Probably the great American epic, with or without its predecessor.

The story of America between the wars, mythologized but far from sugarcoated. Happy ending or no, this is a very dark national portrait but one with a deeply moral core, a morality of personal responsibility and instinctive empathy with the underdog.

Another national portrait, this one covering fifty years instead of twenty-five, and focused on the exceptional and lonely individual rather than the common man and his community. Also a joyride through the medium's possibilities and an anthology of divergent points of view. Brilliant.

This performance short is the greatest "musical" ever made - a brilliantly orchestrated and executed jam session (staged, of course, but full of spirit) with everything you could ask for from music onscreen: dancing, singing, playing, that ineffable "cool." What a gem.

I haven't seen this one for a while, but it lingers in my memory like a powerful, half-remembered dream. A mesmerizing fusion of documentary, personal memoir, fiction, experimentation, and found footage, all of cinema's possibilities are present in one magical work.

One of the great subjective experiences ever put on celluloid. Scorsese, Schrader, and DeNiro make Travis Bickle at once the quintessential loser and an icon tapping into American myths of the romantic outsider, whether cowboy or Indian (see mohawk).

Three great scenes and no bad scenes - actually more than three great scenes, but the three best are so good they outshine everything else: a magical appearance in a doorway, a little speech about a cuckoo clock, and an achingly gorgeous long walk into the future.

A nightmare all the more frightening for being photographed in the light of day, and for having few jumpy moments of shock, just an overall lingering feeling of dread. However, the revelation of the mirror-face still causes a jolt, and the doom-laden conclusion anticipates Mulholland Drive sixty years later.

Never before had the sheer bliss of kids' play been captured with such technical invention or attention to colorful detail. This is, in a sense, the only blockbuster; all others are superfluous.

For my money, the warmest and most engaging Fellini, crackling with a wise romanticism and a sad realism, at once honest and magical. The sad, struggling, yet resilient Cabiria makes a poignant counterpoint to the cool cynicism of La Dolce Vita's Marcello.

28. Fists in the Pocket(1965/Italy/dir. Marco Bellochio)Savage and sensitive, this quintessential sixties film is at once black comedy, biting social satire, violent horror, and pure sensory experience. Subversive and romantic in its roving cinematography and jagged editing. And Paolo Pitagora - oh baby...

29. Goodfellas(1990/USA/dir. Martin Scorsese)One of the most sheerly enjoyable films of all time, eminently re-watchable, at least if you can stomach the endless stream of violence, profanity, and drugs. Full of hilarious little details and frightening moments...no wonder it was so influential.

30. Red Hot Riding Hood(1943/USA/dir. Tex Avery)Another film that could be watched in a loop, and it's easy to do because it's so short and sweet. A horny exculpation of the fast-paced forties life which couldn't be represented in live action, this is a hilarious portrait of sexual frustration and an insanely clever fractured fairy tale.

31. Singin' in the Rain(1952/USA/dir. Stanley Donen & Gene Kelly)Sheer pleasure - not only highly imaginative song and dance, but a story that would make this one of the best comedies of all time, even if wasn't a musical to boot. The hilarious "Dueling Cavalier" fiasco could stand alone as a brilliantly subversive experimental short..."Yes, yes, yes! No, nooo, nooooo...."

32. Easy Rider(1969/USA/dir. Dennis Hopper)The movie doesn't get enough credit for its sense of humor, its raw power, and the impressionistic flow of its images and sounds - if there's a more kinetic use of cutting and pop music this side of Scorsese, I don't know it. And Nicholson's hilarious.

33. White Heat(1949/USA/dir. Raoul Walsh)A middle-aged Cagney turns in one of his most iconic performances as a ruthless killer with a mother complex, an itchy trigger finger, and a penchant for temper tantrums. The rugged scenery adds to the atmosphere and the explosive finale is just right...what a way to go.

34. Band of Outsiders(1964/France/dir. Jean-Luc Godard)Godard's greatest tribute to Hollywood (and acknowledgement of the gap between its aura and his own style). A thriller with one of the great musical moments and a number of winking western references. A girl and a gun - enough for a movie, if not (as it turns out) a successful heist.

35. The Man with the Movie Camera(1929/USSR/dir. Dziga Vertov)Sheer play, making every possible use of the camera and editing shears. Is it documentary? Fiction? Experimental? Home movie? All of the above, and pure movie through-and-through. As much, if not more, a sensory experience as an intellectual one.

36. The Gold Rush(1925/USA/dir. Charlie Chaplin)City Lights is the most iconic and perhaps perfect Chaplin, but this is the one that makes me laugh the hardest, and most involves me - who can't sympathize with the Tramp's humiliation at the mittened hands of Georgia Hale? Starvation, cannibalism and unrequited love have never been funnier.

37. Snow White(1933/USA/ani. Roland Crandall)Forget the Disney version;

this is the fairest of them all. Stuffed to the gills with subversive imagery, clever details, and hilarious gags (hand-animated by Crandall over 6 months), this Betty Boop adaptation sends Grimm packing in favor of the marvelously sustained, rotoscoped brilliance of Cab Calloway.

38. Scarface(1983/USA/dir. Brian De Palma)Raw, garish, and trashy, perfectly capturing the eighties as a blood-red, cocaine-white, Miami-blue visual feast. DePalma, Stone, and Pacino are in (over-the-)top form.

39. Hyperballad(1996/France/dir. Michel Gondry)A music video that can stand with the great impressionistic shorts of all time. Gondry, through his trademark elaborate simplicity, evokes at once the sensations of dreaming, playing video games, and travelling through a strange landscape. Unforgettable images paired with Bjork's evocative soundscape.

40. Daisies(1966/Czechoslovakia/dir. Vera Chytilova)Wildly anarchic, here is a movie that captures the sixties in all its manic energy: playful, destructive, restless, apocalyptic. Chytilova claimed to be condemning the film's protagonists, perhaps to avoid official censorship (no such luck), but the stylistic bravado of this Czech classic is a gas.

41. Through a Glass Darkly(1961/Sweden/dir. Ingmar Bergman)Perfectly captures the melancholy, unsettling beauty of the isolated seashore as well as the tantalizing, terrifying madness beckoning on the horizon and whispering through the cracks of the wallpaper. Harriet Andersson is both hyperreal and ethereal, and the final revelation carries a horrific punch.

42. The Mother and the Whore(1973/France/dir. Jean Eustache)Talk, talk, talk, and cinematic to its core. The nervy energy and youthful restlessness of the sixties meets the ennui and world-weary disappointment of the seventies. An intellectual, sexual, and social exploration, this is the chamber drama as epic.

43. Rosemary's Baby(1968/USA/dir. Roman Polanski)Funny and terrifying, no movie better captures the claustrophic sense of paranoia - because we have no reason not to believe "all of them witches." Like

Taxi Driver (even more so) a brilliant exercise in pure subjectivity. The ending is creepily hilarious.

44. Out 1(1971/France/dir. Jacques Rivette)Another exercise in paranoia, though this time it runs so deep you don't even know

what you're paranoid about. There's no story to hook into exactly, just a relaxed yet alluring mood, an intriguing cast of characters and a series of immersive moments. One hell of an experience.

45. Chinatown(1974/USA/dir. Roman Polanski)No director better captures the frank charisma and brute power of evil than Roman Polanski. As Noah Cross sneers at justice, all the world seems a cruel, mocking Chinatown.

46. The Big Lebowski(1998/USA/dir. the Coen brothers)Looking for a lighter L.A. neo-noir? Already having sauntered from theatrical flop to cult favorite,

Lebowski may be on its way to even greater glory - as both the Coens' masterpiece and one of the most brilliant comedies ever crafted. Made me laugh to beat the band.

47. Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me(1992/USA/dir. David Lynch)Speaking of flops, this was practically chased out of theaters by a lynch mob, less than two years after the TV series had been a smash. Too bad, as it both delivers on and utterly transcends the show's promise. One of the most upsetting and riveting movies ever made.

48. Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid(1973/USA/dir. Sam Peckinpah)The most recent addition to this list - I only saw it a week ago, but boy was it worth the wait. The scene at left: Wow. Screw the Bomb;

this is Slim Pickens' greatest moment.

49. Murder, My Sweet(1944/USA/dir. Edward Dmytryk)The

Stagecoach of noirs - not necessarily in terms of influence, certainly not for star power (Dick Powell is excellent, but Bogie - if anyone - was noir's John Wayne) but for its universe of archetypes. What a rich atmosphere, what an intricate plot, what a tough, streetwise sensibility! What a movie.

50. A Walk Through H(1978/UK/dir. Peter Greenaway)Wickedly bizarre and endlessly amusing and imaginative, this is one of the great avant-garde films. A guided tour through a gallery becomes some sort of metaphysical spirit quest, where ornithology, bureaucracy, and surrealism tangle, under the watchful eye of Tulse Luper.

51. Pinocchio(1940/USA/prod. Walt Disney)Going beyond the iconic mesmerism of

Snow White, Disney and his animators create a rich world and pack the frame with character and invention. The imaginatively creepy Pleasure Island foreshadows the Disney Corporation's sinister evolution, but this time the magic still wins out.

52. Mean Streets(1973/USA/dir. Martin Scorsese)The opening montage, with its fusion of home movies, filmmaking bravado, and the yearning beat and vocals of pop music - unbelievably brilliant. Scorsese knows, in his bones, how to craft kinetic cinema, and here grit and opera combust in glorious fashion.

53. L'Eclisse(1962/Italy/dir. Michelangelo Antonioni)This film has some sort of loose plot, but what it's really

about is the strangeness of that water tower, the delicate shudders of those slender flagpoles, and Monica Vitti's gorgeous gaze at the strange new world around her.

54. 2001: A Space Odyssey(1968/USA/dir. Stanley Kubrick)I love the boldness of the apes and the wiggy trip through the wormhole but ultimately what stays with me are HAL's queerly moving saga and that eerily elliptical white room, maybe the perfect essence of the "Kubrickian."

55. Historias Extraordinarias(2008/Argentina/dir. Mariano Llinas)If

2001 seeks out excitement in the far corners of the solar system, this movie reveals the extraordinary in the everyday. A warm-hearted Whitmanesque adventure, with no dialogue but continuous narration,

Historias truly captures the spirit of good storytelling.

56. The Last of the Mohicans(1992/USA/dir. Michael Mann)More than just a good adventure yarn, this is a masterful exercise in form - with a climax that remains a masterpiece of rhythmic montage. Maybe Mann's masterpiece.

57. Casablanca(1942/USA/dir. Michael Curtiz)A romantic classic, to be sure, and an archetypal piece of brilliantly enjoyable Hollywod entertainment. But it also bottles a particular prewar and early-war sensibility of political commitment and underdog resistance; this put the dream factory on war footing.

58. Annie Hall(1977/USA/dir. Woody Allen)Another comedy that manages to be brilliantly witty, stylistically clever, narratively engaging, and laugh-out-loud funny - not an easy combination to achieve. Apparently crafted in the editing room and through reshoots, you'd think the wandering narrative was carefully planned, so perfectly does it hit every note.

59. The Decalogue(1988/Poland/dir. Krzysztof Kieslowski)Through patient storytelling and seemingly simple yet carefully conceived visual approaches, Kieslowski creates an entire world, or rather ten whole worlds, overlapping but with their own centers of gravity and ways of seeing. Each story is powerful but the sum is greater than its parts.

60. Civilisation(1969/UK/hosted by Kenneth Clark)A groundbreaking history of art and civilization, this is a film which really opens up the wonders of the past - and a mostly passed perspective - for modern viewers. Traditional and eccentric, Clark's enthusiasm is contagious. As one fan said, he "makes you want to look at the stars."

61. Apocalypse Now(1979/USA/dir. Francis Ford Coppola)A wild, hallucinatory ride whose nihilistic worldview fuses Coppola's megalomaniacal grandeur, Milius' militaristic bravado, and Brando's mad insights.

62. Barry Lyndon(1975/UK/dir. Stanley Kubrick)Certainly a close contender for the most visually stunning film of all time, at least the most visually stunning landscape film (though actually its candlelit, NASA-lensed interiors are the equal of those exquisitely exposed hillsides). The last time Kubrick would take his camera so far afield.

63. 42nd Street(1933/USA/dir. Lloyd Bacon, chor. Busby Berkeley)The perfect backstage musical, capturing all the sweat, tears, and sexual tension and transforming them, through some kind of cinematic alchemy, into the most dazzling, inventive (and truth be told, theatrically impossible) musical numbers of all time...at least until the next Berkeley film.

64. The Best Years of Our Lives(1946/USA/dir. William Wyler)Quietly moving, this film deftly mixes the melodramatic traditions of Hollywood with a newfound sensitivity to postwar reality and realism, from the textured characterizations to the evocative small town setting to the deep-focus photography of Gregg Toland (leading to some brilliant compositions).

65. Au Hasard Balthazar(1966/France/dir. Robert Bresson)My first real "holy grail" film; after waiting five years, I was able to see it and was, inevitably, disappointed. Yet over time, almost out of that disappointment, I came to love it. Because Balthazar never asks for our sympathy, the film skirts sentiment and becomes perhaps the most authentically sad film ever made.

66. Rear Window(1954/USA/dir. Alfred Hitchcock)A movie about watching movies (or perhaps the new medium of television), cleverly disguised. What a marvelous little world was created outside that courtyard window, where romance and mystery unfold under orange skies amidst the bustling hum of the Village.

67. The Apu Trilogy(1955-1959/India/dir. Satyajit Ray)From the wondrously naive sensitivity of

Pather Panchali to the formal sophistication of

The World of Apu, this trilogy represents not only the growth of its protagonist but the development of a great filmmaker from his brilliant debut to his quick mastery of the medium.

68. Satantango(1994/Hungary/dir. Bela Tarr)Some movies create a world through the use of space, others through time.

Satantango uses both, but especially time, luring us into a trancelike ambiance where the mundane and mystical intermingle - movie magic of the most unusual kind.

69. God's Country(1986/France/dir. Louis Malle)In the Midwest farm town of Glencoe, Malle discovers unique human truths and universal themes: love, loneliness, work, aging, death, family, rebellion, community. The documentary skirts condescension and sentimentality, without falling into either trap - what emerges is a small masterpiece of humanism.

70. The Seventh Seal(1957/Sweden/dir. Ingmar Bergman)Bergman's seventeenth film became his biggest breakthrough and created iconic images which linger still: a squirrel atop a tree stump, a silhouetted dance of death across a hilltop, and of course a game of chess against the sunrise. I love the boldness of Bergman's ambition.

71. Jaws(1975/USA/dir. Steven Spielberg)The mechanics of the film - its creation of suspense and use of spectacle - still impress, but it's the human drama (and comedy) that keeps me coming back.

72. Scarface(1932/USA/dir. Howard Hawks)That revelation of Tony Camonte in the barber's chair is a masterpiece of economy - to me, it says everything about the Hawks touch. And Hecht's screenplay is a classic: "Get out of my way Johnny, I'm gonna spit!" sprays "Say hello to my little friend!" with a hail of bullets and leaves it for dead.

73. Ivan the Terrible, Part II(1946/USSR/dir. Sergei Eisenstein)Lurid and decadent, this is one of the most bizarre big productions of all time. It pulsates with a kind of psychosexual energy, manifested in the craggy, expressionist sets, the distinctive Prokofiev score, Eisenstein's chesslike directorial conceptions, and Nikolai Cherkasov's baroque performance.

74. Gone with the Wind(1939/USA/dir. Victor Fleming & George Cukor)I guess some people don't dig it, but how can you not? To me it seems the essence of Hollywood - glorious colors, larger-than-life characters, an epic story. There's irony too; as Mark Cousins notes in

The Story of Film it's an escapist film whose narrative content explicitly condemns escapism.

75. Pandora's Box(1929/Germany/dir. G.W. Pabst)Nothing can quite prepare you for your first sight of Louise Brooks. She bursts into the room, long sleeves trailing behind her, smiling with a deadly lack of guile. No dramatic buildup is necessary; the force of her personal attraction leaps across the decades and through the screen to lure you to your doom.

76. La Roue(1923/France/dir. Abel Gance)Through a sense of montage that is more about accumulation than tension, Gance evokes a universe of passion, frustration, violence, and loneliness. With the sensitivity of his direction and the gusto of his technique he transforms potential melodrama into the stuff of Greek tragedy.

77. The River(1951/India/dir. Jean Renoir)And here we have one of the great dissolves in cinema history - from an older man, philosophizing about how death is a release from the burden of life to a young girl, sunk into grief; thus simply and subtly Renoir undercuts spiritual rationalization with simple human emotion.

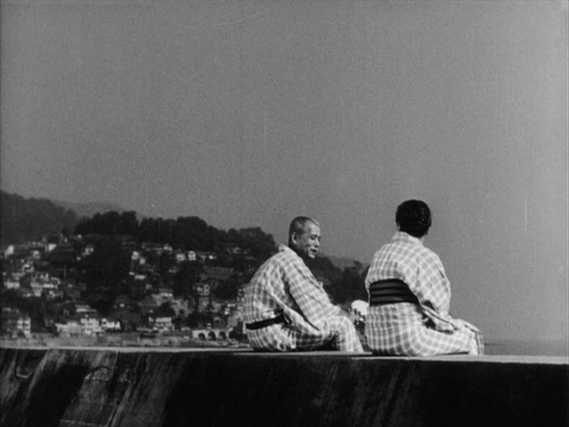

78. Late Spring(1949/Japan/dir. Yasujiro Ozu)Every time you see it, something new strikes you - maybe the devastating apple peel at the end, or the crushing weight of the Noh performance (which often strikes Western viewers as tedious at first glance), or the poignant final sleepover at the resort. A film full of little truths that grow on you.

78. The Wizard of Oz(1939/USA/dir. Victor Fleming & King Vidor)A movie that, almost by accident, seems to contain everything: a childlike fairy tale, an all-American fable, a political allegory, a psychological code, a psychedelic experience, a dreamy invocation, a quintessence of elusive Hollywood alchemy. Even pulling the curtain on the wizard only deepens the mystery.

80. The Adventures of Robin Hood(1938/USA/dir. Michael Curtiz & William Keighley)Lavish Technicolor, giddy swashbuckling, hearty humor, Olivia de Havilland's beauty, Claude Rains' devious charm, Errol Flynn's jaunty swagger - and added to all these attractions, an eccentric plot twist gives Robin a refugee camp to run, bringing him up to date in a world consumed by war and fascism.

81. The Civil War(1990/USA/dir. Ken Burns)Though his approach has become somewhat formulaic since, this immersive, empathetic historical experience still feels fresh. The miniseries constantly makes the period vivid, reminding us, especially through astonishing sound film footage of veterans - that the war was not so long ago or far away.

82. The End of Evangelion(1997/Japan/dir. Hideaki Anno)Even knowing the preceding anime TV series, it can be difficult to make heads or tails of the avant-garde, apocalyptic imagery cascading across the screen in this feature follow-up. Nonetheless, it remains a mesmerizing visual experience and thought-provoking metaphysical exploration.

83. Syndromes and a Century(2006/Thailand/dir. Apichatpong Weerasethakul)A dreamy meditation on the differences between city and country. Halfway through, the film radically transforms its texture, switching from the warm greens of a rural clinic to the cold whites of an urban hospital.

84. Raging Bull(1980/USA/dir. Martin Scorsese)Part gritty neorealism, part psychodramatic myth, Scorsese fuses disparate historical and cinematic traditions to produce a cold-blooded, hot-headed masterpiece of craft, one of the last great films of New Hollywood. The fight scenes remain expressionistic classics.

85. Schindler's List(1993/USA/dir. Steven Spielberg)By choosing an uplifting story about a historical tragedy, and by telling this story in a gripping and entertaining fashion, Spielberg invited criticism - but these potential flaws are also the film's great strengths, along with Ralph Fiennes' mesmerizing, terrifying performance.

86. Miraculous Virgin(1967/Czechoslovakia/dir. Stefan Uher)A poetic Slovakian masterpiece about war, art, and the power of beauty - full of surreal touches, conveyed especially through the movement of the camera rather than aggressive editing or Kafkaesque narrative devices.

87. Platform(2000/China/dir. Jia Zhangke)A brilliant depiction of China's rapid transformation from Maoism to capitalism, provincialism to globalism, tradition to rootlessness. Throughout mobile tableaux, little details (a hairstyle, a song on the radio) accumulate until nothing remains the same.

88. Place de la Republique(1974/France/dir. Louis Malle)On a day like any other, Louis Malle and his camera crew enter a public square and begin filming and interacting with the people they run into. Before long, fascinating stories and amusing personalities emerge: cinematic intrigue naturally arises from the everyday.

89. Stop Making Sense(1984/USA/dir. Jonathan Demme)Through a concert film so carefully (yet subtly) staged as to rival the biggest Hollywood musicals, Talking Heads offers both a captivating performance and a sly narrative about a loner joining a community. David Byrne must be seen to be believed.

90. Cria Cuervos(1976/Spain/dir. Carlos Saura)Ana Torrent gives an incredible performance as a little girl whose resentment of her father leads to a mixture of confused guilt and murderous pathology after he dies. Shot around the time of Franco's death, this is psychological drama with political implications.

91. Faust(1926/Germany/dir. F.W. Murnau)Giddy with the inventiveness of its images, this Expressionist classic finds time to both evoke the iconography of the Middle Ages and playfully indulge in pastoral romances and farcical roundelays. The tone shifts repeatedly throughout, soaring through epic, horror, romance, and comedy before its dramatic conclusion.

92. Emak-Bakia(1926/France/dir. Man Ray)Ray captures a fluidity already suggested by his photographs in this experimental short, objects, people, and abstract images shift and transform before our eyes; anticipating Vertov by a few years, Ray even shows a camera-eye. Self-conscious perhaps, but this is an exercise in pure sensation.

93. All the President's Men(1976/USA/dir. Alan Pakula)A moody, evocative thriller, low on violence yet high on tension and atmosphere. Pakula's mazelike sense of intrigue, William Goldman's compelling mind-puzzle screenplay, and Gordon Willis' shadowy photography evoke a tangled world of corruption.

94. Death by Hanging(1968/Japan/dir. Nagisa Oshima)Caustic, clever, and finally, almost surprisingly, compassionate, Oshima's satirical masterpiece centers on a Korean criminal who, physically, simply can't be executed. Surrealistically investigating and re-enacting the crime, the officials end up implicating themselves.

95. Persona(1966/Sweden/dir. Ingmar Bergman)Images and strange dialogue stream forth from Bergman's subconscious, disciplined by two decades of filmmaking experience yet raw with the urge to communicate an elusive experience. Whatever you make of the strange sequences, they carry a kind of dreamlike charge.

96. Dogville(2003/Denmark/dir. Lars von Trier)Perverse, exhausting, and exhilirating, von Trier's theatrical-yet-cinematic approach & stripped-down sets create a captivating if cruel emotional reality.

97. Celine and Julie Go Boating(1974/France/dir. Jacques Rivette)A film that stubbornly evolves its own logic: two young women trespass in a house that seems to exist in a parallel universe - or a parallel movie. They begin to interfere with the drama that unfolds there, abandoning their own narrative to play around in another.

98. Lost in Translation(2003/USA/dir. Sofia Coppola)Snobby? Self-centered? Perhaps. But is the film as "boring" as its legion of detractors seem to find it? Quite the opposite: I know few movies so absorbing. If you tune into Coppola's frequency, every moment is pregnant with a mesmerizing, melancholy mood.

99. La Haine(1995/France/dir. Mathieu Kassovitz)A joyride and a cri de coeur,

La Haine brilliantly varies between long-take, static-shot dead-time and explosively kinetic camera movements and cuts - the characters' only relief arriving via confrontation with the cops or the sonic deliverance of hip-hop.

100. La Vieja Memoria(1979/Spain/Jaime Camino)This documentary on the Spanish Civil War is mostly talking heads - yet somehow this only adds to the fascination and the human drama. The title is Spanish for "that old memory" and, watching these faces forty years after the main event, it's as if we are digging through the sands of time, excavating what remains of the truth.

Many of these films were featured in my video series. Visit

Cinema in Pictures to browse video clips by title.

This is a Top Post. To see other highlights of The Dancing Image, visit the other Top Posts.

.png)