Who are the fortunate ones who gain the love they seek?

When I asked for flowers, I was given thorns.

Who are the fortunate ones who gain the love they seek?

When I searched for happiness, I was lost in streets of sadness

When I sought songs of joy, I heard songs of sorrow.

Every torment doubled the pain of my heart

When I asked for flowers, I was given thorns.

Who were the fortunate ones who got the love they sought?

Companions came, stayed awhile, then left me all alone.

Who can spare the time to clasp the hand of a falling man?

Even my shadow eludes me as it fades away.

When I asked for flowers, I was given thorns.

Who are the fortunate ones who gain the love they seek?

If this is called living, then I'll live my life somehow.

I shall not sigh, I'll seal my lips, I'll dry my tears.

Why should I fear grief, when I have encountered it so often?

When I asked for flowers, I was given thorns.

Who are the fortunate ones who gain the love they seek?

I entered

Pyaasa blind, knowing only that it was considered one of the classics of Indian cinema. I haven't seen any other Guru Dutt films (in fact only afterwards did I realize Dutt himself played Vijay, the poet protagonist who struggles against a hostile world) and haven't seen a great many Indian films; only recently have I been making a conscious effort to explore this rich corner of the cinematic globe. I wasn't even sure when

Pyaasa was produced, only locating it in the late fifties when a young character referenced his graduation from college in 1952. The viewing experience is often enriched by such ignorance, as it certainly was here. In any case, despite many distinctly Indian touches - including, of course, the casual breaking-into-song outside of what we would consider ordinarily musical scenarios -

Pyaasa's story and themes are universal, and I found its pathos in many ways

more relatable than the world presented on American screens in the 21st century.

Pyaasa is as moving and enchanting as ever, a powerful fusion of cinema's illusionistic and reflective tendencies. Laced with dazzling musical numbers, sumptuous sets, comedic asides, swooning romantic interludes,

Pyaasa is also penetrating in its social critique, empathetically embedded in the perspective of the downtrodden, and at its heart is, well,

heart: a genuine, earnest investment in what is being offered to us.

When the movie opens, Vijay is lying in a field, feeling the sun's warmth on his skin, eyes flitting around the sky and foliage pleasantly enjoying nature's generous bounty and singing on the soundtrack of his peace in this brief moment. Short-lived, of course. He (and we, echoing his perspective as we will throughout this very subjective film) smiles as he watches a bee zip from flower to grass, only to see the bee crushed underfoot: a cloud crosses his expression and will remain there throughout the movie, unrelieved even through the final reel. Removing himself from his respite, he leaves the park and enters the street, heading to a newspaper office where he hopes his poems have been accepted for publication. They have not. Brecht once sagely commented, "Every day, to earn my daily bread I go to the market where lies are bought. Hopefully I take up my place among the sellers." Vijay does not take his place among the sellers; and while he is presented and presents himself as an idealist throughout, it seems clear that he couldn't sell lies even if he wanted to (and sometimes he does). It isn't in his constitution, which is often more of a curse than a blessing.

Vijay's brothers scorn him for being a "layabout," unwilling (or more likely, unable) to secure a living and support his family, a burden they must take up themselves. His mother loves him still, but he is ashamed of relying on her and leaves her weeping to seek shelter with friends, who send him into sexile when prostitutes come calling (cannily selfish, they have long ago mastered the art of selling lives for survival - when Vijay reminds one of them how he compassionately mending an animal's broken leg once, the friend wryly comments, "I was a child then - and you still are."). Eventually, hair matted, collar upturned, coat shabby - poor but with the lingering, bewildered appearance of one once educated and optimistic - Vijay makes his bed on park benches, sullenly contemplating the fact that his poems were sold for waste paper, and catching glimpses of a former love who married into society. He works here and there, where he can find it, gradually realizing that unemployment has become not a starving-artist lifestyle choice but an inevitable consequence of his inexperience and personality. Indeed, others - including a comic-relief traveling masseuse - are able to profit from Vijay's labor, using songs he's written to woo customers; we sense that his failure is less due to the quality of what he's selling than his own inadequacy as a salesman (and discomfort taking on that role).

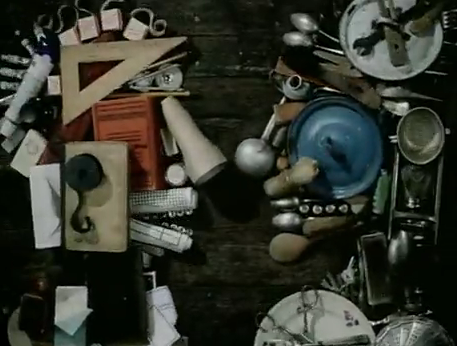

Eventually Vijay finds work at a publishing house, as an assistant to successful artists and publishers, most degradingly asked to serve drinks at a bourgeois house party where poets prattle on about their abstract commitment to society while ignoring his presence in the room; he isn't one of the "fortunate ones" like themselves, he doesn't matter. When he breaks into the above song, a few of the guests are amused and one asks, with a sort of patronizing thoughtfulness, "Why can only the rich be poets?" and encourages the servant to continue. As Vijay lays his heart bare, the others drift about the room, listening and ignoring at will. Only three people seem to have been really paying attention when he finishes: a random stranger, who impulsively bursts into applause and then embarrassingly halts when he notices no one else is impressed; Vijay's boss who scowls from his seat before getting up, recognizing a pernicious subtext to the singer's recitation; and finally, the boss' wife Meena (Mala Sinha), sorrow-stricken - for she was in love with Vijay in their student days, and abandoned him to marry her rich but unromantic husband: this is the hidden meaning the master of the house recognizes.

Like many an entertaining melodrama,

Pyaasa (whose title means "Thirsty") ties its social observations and personal angst to a romantic storyline - two romances, in fact. One is between Vijay and the boss' wife, his former lover, although he - through a mixture of honor, pride, and compassion - refuses to resume his affair with her. The other romance, also held off from consummation and also uneven in its distribution of action and affection, is between Vijay and a prostitute, Gulabo (Waheeda Rehman), he meets early in the movie. Her emergence is arresting - she appears in a park where he lies on a bench and begins singing his own words to him (not knowing they are his own words; she discovered them while purchasing waste paper and, like the masseuse, uses them to attract potential clients). She is at first the iconic object of the classic male gaze, a goddess floating across the screen with alluring gestures, seemingly a projection of pure desire, both holy and unholy: but this an act, a show she puts on - her own Brechtian lie to earn her daily bread. When she discovers Vijay is more interested in her song than her sex appeal, and unwilling/unable to pay for an encounter, the hard-edged sex worker peeks out from the gauzy facade and angrily ejects him from her hovel. Only later, realizing that he was the author of those beautiful words she sang, does she soften and seek to care for him (offering food, a place to stay, and eventually her companionship in his sad, strenuous life - something his previous lover refused).

At a glance,

Pyaasa is full of cliches - pure and suffering starving artist, scornful family eager to cash in once the black sheep pays out, grieving mother destined for an early grave, selfish gold-digger placing position over passion, and of course the hooker-with-a-heart-of-gold. Yet cliches are only as egregious as they are rote, and

Pyaasa is deeply invested in its characters and themes; not for nothing (one suspects) did Dutt cast himself in the title role. The film is emotionally resonant not only because it believes in its story but because we are able to recognize reality in its folds of fantasy too. There are also numerous subversive gestures humanizing characters who might be mere wallpaper in a many other entertainment films. When Vijay drowns his sorrow and visits a brothel, his bleary revelry is disrupted by the cries of an infant behind the dancing girl's curtain backdrop. She would be an element of style in many other movies, but here she is allowed personhood as is everyone - even many of the villainous characters - in this profoundly humanist work.

I have mixed feelings about the final act (spoilers ahead) in which Vijay seems to "die" in an intended suicide turned botched rescue attempt. Having given his coat to a beggar, who follows Vijay into the railway track and then gets his foot caught in the rail as a train approaches, Vijay struggles to free the man and is apparently unsuccessful. At first we don't know who was killed, but since only one body is found, that wearing the coat and presumed to be our hero, we can assume that Vijay lives. And sure enough he does, confined to a hospital, at first amnesiac until his sense of self is reawakened by a nurse reading his poems aloud. It seems in light of his tragic and spectacular demise, his work was published and he became a "posthumous" success; in images dramatically echoing Christian iconography a "resurrected" Vijay re-emerges at his own memorial service, is eventually identified by greedy friends and family (who denied him recognition when he was more profitable as a dead man), and then denies his own identity, horrified by the spectacle of avarice and shallow celebrity his fame has wrought. In the end, he leaves, entering into (we gather) a permanent wandering exile with Gulabo - inverting the Christ myth by sadly leaving the society he hoped to save.

My ambivalence stems from the way this conclusion flamboyantly upsets the delicate balance of what's came before, as Dutt matched a sense of joyous engagement with life with a sober awareness of its crushing hostility and indifference. I don't particularly like the way the homeless man becomes a prop to set up Vijay's own dramatic reversal (although this is tempered by the ambiguity of said reversal), and as Vijay becomes more and more Christlike he loses some of what made him, even as a noble idealist, so touchingly human. Meanwhile, the brothers, the boss, and Vijay's friend become a bit more one-dimensional than they were before: earlier we could comprehend, for example, the brothers' angry resentment at the prodigal son but now they simply become cartoonish connivers out for a fast buck. All in all, I found

Pyaasa more evocative when it focused on the man who will never be good at selling lies than the man who chooses not to.

That said, Dutt's willingness to follow the "rags and riches" story to its logical conclusion, only to subvert the expected happy ending, is certainly brave. It makes the film's rejection of shallow glamor and hollow acclaim all the more effective. This twist also allows Dutt to pay homage to further cinematic influences, adding to the mix traces of Fellini's showmanesque penchant for false miracles and the topsy-turvy class and identity games played by

Sullivan's Travels. Already the film has inventively fused the trappings of Hollywood melodrama (especially those of the Depression, which focused on social tensions later elided) with the sensitive but not particularly optimistic social consciousness of Italian neorealism. There are also echoes of

Pyaasa in later films I've seen, almost certainly unintentional but evidence that Dutt's film is floating on a long stream of cinematic humanism and compassion.

The film that leaped most immediately to mind was

Tender Mercies, the last feature film I watched before

Pyaasa, another story of an artist living a life of struggle and quiet, everyday humanity. In

Tender Mercies, Mac Sledge (Robert Duvall) is post-fame, rather than pre-fame; having given up drinking and his abusive relationship to his first wife, he is somehow making amends by hiding from his celebrity and even (with greater difficulty) his craft, only writing songs on the sly and resubmitting them for recording with hesitation. After a personal tragedy, the country singer confesses, in one of the most moving lines I've encountered in a movie, "I don't trust happiness. Never have. Never will." Vijay's story, set in the crowded city, is deeply aware of society's structures and practices and how this twists everyone into cruel, selfish, desperate purveyors of self-protecting lies. Mac's story, laid out on the empty frontier, is more elemental in its feel, more personalized in its sense of guilt and temptation: the enemy is within.

What Mac and Vijay share is the recognition of their art as a "gift" instead of a commodity; having just begun Lewis Hyde's book

The Gift, which focuses on this contradiction deeply embedded in modern society, I recognized the connection immediately. The characters shift uneasily between a sense of frustration with the indifferent world, and a weariness of the terms on which the world will consider accepting what they have to offer. Vijay himself quotes Christ in the film's climactic song, pronounced as he reveals his identity amidst a throng of admirers enamored of the mythic artist but indifferent to the actual man before them: "What profits it if a man gains the world?" The remainder of the quotation, of course, hardly needs to be spoken by him: "...if he loses his soul?" What remains affecting about these films, and cuts them off from contemporary cinematic sensibilities, is the passionate fervor with which they believe men have souls to lose.