The how & why of my adventure in filmmaking, followed by the end result...

Commencement: Discovering a Premise

My long journey began in, of all places, Hollywood.

Not behind the closed doors of a cushy studio office, or in a limousine winding between the (literally) star-studded sidewalks, nor even on a sweaty camaraderie-boosting soundstage but at a wings joint on Sunset Boulevard. It had been nearly two months since my quixotic arrival in Los Angeles, but this was the first time I had actually gone out in the city itself, after weeks of scrambling to find a place to live and work. Now, as the clock rolled past midnight, and April gave way to May, I was unwinding with co-workers after a stressful week

Having finally secured a position at a fundraising organization, I set to work immediately pursing my real goal, making movies, only to discover, like the characters in Godard's tragicomic

La Chinoise, that what I thought had been a great leap was only the beginning of a long march. Additionally, the week had seen my blog disappear into thin air (later

resolved, although at the moment my prospects appeared bleak) and offered reminders that, even once hired "permanently" this high-turnover job was hardly a sure thing (indeed, within a few days, I'd be the only one at this table left at the office).

Tonight, the talk quickly shifted from work to movies - street fundraisers, like all impermanent employees in this city, tend to be supplementing work, or dreams of work, in the entertainment industry. I turned to a younger co-worker, who had earlier claimed many story concepts he didn't know what to do with (in other words, the exact opposite of my problem), and asked him if he had any short film ideas he'd be willing to share.

He responded, "Yeah...I haven't written much on it, but I'd love to see a movie about a bunch of characters waiting at a train station for the afterlife. It wouldn't be about where they were going or what happened when the train arrived, but what they were thinking, and who they were."

With that, the wheels began to turn...

Class Notes: Hunting for an Angle

The initiation of this project in an atmosphere of camaraderie and collaboration is ironic, since so much of what followed was pursued alone. For months I would sit outside my home in a peeling lawn chair from the 1970s, filling journals with excessive notations, more often meanderings than epiphanies. Initially, however, the eurekas outnumbered the dead ends. Among the former: there would be five characters, they would have something else in common beyond being dead, they would in fact be classmates reunited in the afterlife on the cusp of their living peers' tenth reunion (something I'll discuss more extensively in this piece's conclusion), and there would be a sixth character, Jacob, an outsider - either newly dead or not dead at all - who encountered these characters in an out-of-body experience, or a dream (much like the Biblical Jacob, watching angels ascend a ladder to heaven in a wilderness vision).

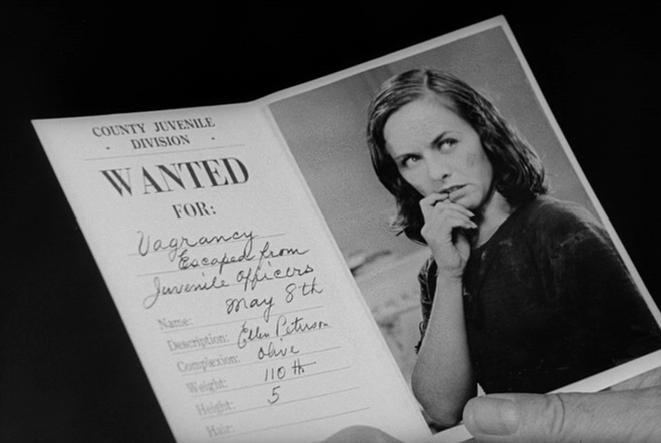

Above all the characters were clear to me right away, and I never wavered. The first was a mysterious, alluring girl who was the center of attention but preferred to be left alone, only to be horribly murdered soon after high school (

Twin Peaks' Laura Palmer was an obvious inspiration here, but so was an afterschool special - or was it a dream? - I saw as a very young child, which has haunted me ever since, in which one day a girl simply disappears and is never seen again). The second was a likable guy who kept his regrets and anxieties to himself, eventually joining the Marines and dying in Iraq (many close friends, relatives, and acquaintances have gone overseas in the past five years, something I think remains an underrepresented phenomenon in contemporary cinema). The third was a brash, confident scholar and athlete, full of charisma and felled by cancer (sadly, I've known too many who have gone this way and always been deeply disturbed by the external, physical transformation following the various treatments). The fourth was a perpetual loser, bullying in childhood, druggily withdrawn in adolescence, and despairingly afflicted in youth before committing suicide beneath a Boston train (something that used to happen all the time when I lived there; the character himself, with his addictions and struggles with mental illness, is familiar to me and somehow he was always the one here who fascinated me most). The fifth and final was a fun, easygoing, down-to-earth teenager turned young mother and long-suffering wife, killed routinely yet gruesomely in a highway accident alongside her son (emblematic of so many peers of mine, whose leap into the responsibilities and rewards of parenthood is both something that astonishes me and something that I've gotten used to - and probably the element that most represents to me the growth, change, and maturity these characters undergo).

As noted, there were dead ends too and they were eventually prevalent. I couldn't figure out what these characters had to say to one another, and I turned to other story structures for inspiration, eventually flirting with writing the film as a feature. I even patterned one version of the story after

The Wizard of Oz with Jacob dreaming he's back in high school among now-much-younger teenagers (Munchkins), assigned by his slightly obnoxious ex-class president turned school principal to track down an inspirational teacher who died when they were all in school. Jacob would take a yellow school bus to the eccentric teacher's luxurious home, picking up his classmates, each embodying a quality he needs or lacks, and arriving at the teacher's doorstep only to discover that the typically pie-in-the-sky baby boomer has nothing to offer him or his peers, nothing that can relate to the lives they are living/have lived anyway. Potentially pretentious if not handled with the right amount of humor, this idea was - more importantly - wildly impractical under current conditions.

It was around this point that I suggested to myself a photo-montage opening in which we saw pictures from the characters' pasts, perhaps set to music, and maybe even a bit of narration as Jacob recalled who they were. Whatever followed this exposition would be another matter; this sequence would crystallize who these people were and where they came from. The more I thought about this idea, the more I liked it and eventually I realized, with a bit of shock at how easily this simple, natural notion had hitherto escaped me, that in fact

this was the movie I wanted to make. And, as an added bonus, it would be a hell of a lot easier than hiring a schoolbus and shooting a feature film. The film had always essentially been about the characters. Now it would be so emphatically.

Graduation Speech: Writing the Narration

With this, I was relieved of the duty to write dialogue, and assigned a new challenge: craft a narration that could carry the piece and articulate the narrative details and character descriptions without being overbearing. A tall order, since every budding screenwriter is taught first and foremost to avoid voiceover. Here I was writing a film that was nothing else.

And so I dumped the afterlife angle. I waved goodbye to the train station, although eventually it snuck back in, allusively, as the intro to the finished film. I abandoned the

Oz revisions, separated the characters from one another, and returned to what had always compelled me most: not what happened after their deaths, but what happened before then. I wondered if I should reveal right away that they had all died, and ultimately decided against it - the film would be dark and tragic enough without casting the narrative in a bleak, grim light right away. Better to experience the disappointment alongside the narrator, even as we suspect what's coming (something I certainly did not go out of my way to conceal).

Meanwhile Jacob remained elusive. He only became clearer to me when I inserted him more explicitly into the story he was telling, by revealing that he was in fact the neglectful, alcoholic ex-husband he had been referring to in Leah's story (a development that arose naturally as I wrote, surprising me when it came out). With this it became clearer and clearer that the narration would not only be a loosely connected collection of short stories, but the indirect biography of Jacob himself, revealed in glimpses and allusions throughout. Making Jacob Leah's husband and the father of her children also gave him a narrative journey, something that had been lacking in earlier drafts - and while the conclusion remains bittersweet at best, the fact that he is now raising a daughter at least lends a kind of stoic acceptance to the tragic tale.

With so many directions I could go in, so many details to include or avoid, I decided I needed some discipline. Around this time I was watching Hollis Frampton's films (

nostalgia in particular, with its narrated memories over slowly burning photographs was an obvious inspiration) and flirted with some structuralist conceits to keep my short film within fruitful limitations. Among other conceits were, formally, a focus on the number ten (10 years since graduation, and also "20" divided by "02") and, thematically, a vague correspondence to the Old Testament story of Jacob (beyond just the narrator's name and the Jacob's Ladder-like dream). Ultimately, after focusing my energies and explicitly inspiring a few passages or gestures, these helpful if potentially silly hooks were either abandoned or submerged, although the discipline required to write a 10-minute narration helped me to economize immensely, creating much of the text I would eventually use for the finished film.

The most lingering influence of these structuralist devices was actually on the characters' names, which had fluctuated wildly until this point but never changed again even when I sometimes wanted them to, embarrassed by their arbitrary genesis. They all include the letter "J", which is the tenth letter of the alphabet (and of course, the first letter of my own name) - variously as first, last, middle, married, and nickname. And they are all named, first or last, after the characters from Jacob's tale in the Old Testament with whom whom their personalities correspond.

School Portraits: Casting the Project

Around the end of August, while job-hunting and trying to make use of my unexpected free time, I cracked down on my writing. A few days, here and there, I headed to a city park and sat down on a bench or a large tree branch to write, and write, and write - sometimes literally from sunrise to sunset. In this fashion, I hammered out the first true draft of the narration, after scribbling around the edges for months. Now my characters finally existed on the page, and it was time to make them a reality in the flesh.

I posted a listing on the L.A. Casting website a few days after attempting something similar on Craigslist. That first effort had been a complete dud - a posting on a community board asking if anyone had pictures they wanted to share for a film project, describing

Class of 2002's purpose and approach. Crickets - I did not receive a single response.

Knowing that there would be nothing for them to "perform" per se, I had initially been hesitant to specifically approach actors. But I eventually decided that, more than anyone else, they were willing to put themselves out there, would be happy to see their images in circulation, and might view the choice and submission of photos as an opportunity for creative collaboration. It turned out I was right. I posted a casting call for

Class of 2002, filled with brief descriptions of each character by age range and personality, and within days I had a few hundred submissions, especially for Rachel (anyone who has ever posted a request for young actresses age 18-30 has probably experienced a similar deluge). As I corresponded with actors, the field winnowed of course, in part from self-removal, as actors discovered they would not be acting, or simply never responded to my initial messages. Yet in the end, enough people remained for choices to be necessary, certainly an advantageous position for any director to be in.

Really, I had remarkable luck. Some of the characters I thought would be trickiest to find sent the first and most enthusiastic emails to greet me in my inbox. Regan Young, who was cast as Jules, not only had copious photos of his stint in the Marines (in both Iraq and Afghanistan, though I eventually used only the former), he was excited about the project and wanted to meet right away to discuss further. Kevin Mosteller was the only person I ever really considered for Jared; the photos from his teen years perfectly captured that stumbling rebellion embodied in the character's inwardly hurt but outwardly confrontational personality. And as a working voiceover actor expressing interest in Jacob's narration, he turned out to be the perfect two-for-one (especially since I had always seen Jacob and Jared as two sides of the same coin).

Leah and Rachel were trickier; a lot of actresses expressed interest and each offered different qualities. Eventually I chose two Stephanies. Stephanie Rojas exhibited a warm, friendly quality in her photos conveying the comfort Jacob both resists and is drawn towards. Furthermore she had numerous pictures with her adorable nephew, whose cheerful screen presence adds another layer of regret and sorrow to the revelation that Jacob has lost both a wife and a son. Stephanie Hunter faced the toughest competition of anyone, since Rachel received the most submissions. A bit younger than the other actors who submitted (many of whom were actually Class of 2002), she nonetheless won out in the end because her very strong screen presence. And she had lots of these photos too, submitting more than anyone else and confessing that since she was a kid, she'd had a camera glued to her hand. An added bonus: she was the only person who had home movies available, which served as a melancholy punctuation in one of her characters' sequences.

Finally, there was R.J., the trickiest of them all. Initially, she was not only a star school athlete but a potential Olympian. Her dogged determination on the racetrack was one of her most essential features, and an important visual trait in what was, after all, a movie rather than a written text. As it turned out,

nobody had running pictures. Until the end, I clung to this feature, turning eventually outside of L.A. Casting, to my friend Morgan Magistro-Capuozzo, who is not an actress but whom I'd included in a few past projects. She had run cross-country in high school, and graciously agreed to join in at a very late date. As it turned out, she actually couldn't find any running pictures, yet I'd unexpectedly struck gold because in so many other ways the images she provided embodied the determined, gritty, headstrong persona of R.J., who - as it turned out - had been there in front of me all along. I ended up probably using more of Morgan's pictures than anyone else's.

Casting dragged on through November, as the actors patiently waited for me to confirm with them and I struggled with computer problems and a heavier work schedule. I had eventually set a deadline for myself of late December, and yet as Thanksgiving passed and the last month of the year drew nearer, I had not even begun editing the project yet. I cut a very rough trailer at the end of the month, but all of the work lay ahead and increasingly began to seem very intimidating. Had I bitten off more than I could chew? Was the entire project an ill-conceived mess, a complete folly? Would circumstances, particularly the used Mac from hell, sink the film before I could even kick it off? I began to wonder.

Homecoming: Getting Close to the Big Push

For years, I have simply loved editing. It's when everything comes together for me, when I can see the pieces click and the magic start to happen. Preproduction can be hell, as the finished result remains abstract and doubts confront one at every opportunity for procrastination. Production is trial by fire, a rewarding tonic inasmuch as problems must be worked through and cannot be avoided, but emotionally draining, physically exhausting, and mentally intimidating. Postproduction, on the other hand, has all the virtues the other two stages don't. The raw material is all there, and does not need to be conjured from thin air. I've always done my best work reacting to something; this is true of my writing as well as my filmmaking - I love bouncing elements off of one another and figuring out new ways to put them together. Meanwhile, to a certain extent in editing time is more free, and one has to ability to explore and experiment, no longer quite so limned in by the demands of cast and crew or the restrictions of time and money.

One of the perks of

Class of 2002, once I got past my excitement with the idea itself and began to recognize the practical benefits of my approach, was that it skipped over the stress and failures of production and allowed me to create the entire film at my own pace in the editing room. And yet, as winter hit sunny California and my self-imposed deadline crept closer, I felt increasingly anxious and neurotic about the film's prospects, the approach I should take, and where/how I should supplement the photos with other material, from home movies to stock footage, to original footage shot by myself or friends/family I unsuccessfully commissioned to casually produce "second unit" b-roll (in only one case did this come to fruition, as my buddy Jeremy Lampert captured vivid images of Philadelphia from his cell phone).

Since I'm supposed to be promoting the finished product, and myself as a filmmaker, I will avoid rehashing my own missteps and miscalculations here. Suffice to say it was only in the second half of December that the ball really got rolling. About a week before Christmas, Kevin generously leant his time and drove over to Pasadena for what turned into a marathon recording session, stretching till 11 at night. His patience still astonishes me especially since we ended up recording the entire narration in the cramped quarter of his car, where the acoustics were better than the garage I'd originally planned on using. Through multiple takes and my own at times meandering attempts to convey what I was looking for, Kevin responded extremely well to direction and gave me the essential spine of the film, upon which it would rise or fall.

One of the reasons the recording and editing of the project had been perpetually delayed was that I was not yet satisfied with the shape of the material. After focusing for a while on the need to economize, I returned to the text in early December for the first time in months and began expanding it instead. I wrote a much longer version of every character's story, more novelistic than cinematic in texture (out of this arose the R.J. 8th grade party anecdote, some new and more effective opening lines, and the much-extended Leah passage in which Jacob recalls the places they lived, which turned into my favorite bit in the entire film). Then I contracted this down again into a more manageable size, which was used for Kevin's recording.

Yet in the end I probably cut more than half the material Kevin recorded. Only hearing some of the words read back to me, did I realize where and how I'd overwritten - some of the revisions were made right there in the car but the bulk were crafted in the editing room by cutting short and rearranging various lines. It was amazing to me how much I

didn't need to get my point across; I'm glad I wrote and recorded as much as I did, to give me flexibility, but it was chastening to be reminded how few words it takes to convey a point.

Meanwhile, the film's visual texture was coming together. Just before recording the narration, Regan had offered up a dozen or so videos from his time in Iraq and I realized right away that these would become a very important part of the finished film, as indeed they did. The range of visual texture and captured experience was astonishing, capped by a video documenting his re-enlistment at a base in Iraq, with gunfire sounding in the background. While the film's backbone would remain the narration and still snapshots, I knew these dynamic video visuals would do wonders to draw the viewer in and lend a sense of visceral vitality to the picture.

Final Exams: Assembling the Movie

In the last week and a half of December 2012 (December 21, my initial deadline, had come and gone) - particularly the week between Christmas and New Year's Eve - I threw myself into editing, feeling that I finally had all the elements in place. Initially this consisted of cutting a trailer, arranging and cutting down the narration until I felt I had eliminated all the fat, examining all the videos I'd received from Regan, and importing some new, last-minute photo additions. Finally, on the last weekend of the year I discovered a public-domain website which would serve as my video salvation (since most of my requests for outside b-roll had fallen flat). Initially, I used this sparingly, punctuating each character's intro with a brief moment from some of the more casual stock footage.

The real find, and the sort of inspirational kick in the pants worth much more than just its tangible effect on the project, was a fifties documentary on the area I grew up in! All along I had wanted the characters to be from New England, and had even included explicit references to Massachussetts towns in the narration (although much of this was cut, some remains). And here was my home, filtered through the haze of an old-fashioned documentary, both familiar and displaced. I ended up using many images from this footage, especially in the second half.

I set aside a Saturday strictly for this film (this was, in fact, to be my very last day off from work; I'm not scheduled for another until at least February). As they tend to do, all my doubts and worries crept upon me and I found myself rearranging ambitious plans to go drive all around the L.A. area to film b-roll, instead limiting original footage to the beginning of the film, to be shot during sunrise at Angel's Flight Railway (a historic wooden track up a steep hill in downtown L.A.) and the ending, to be shot during sunset at the Santa Monica pier.

That evening, December 29, I headed to Santa Monica armed only with my iPhone and began shooting. Though the camera is not HD and some of the interior footage was unusable (including b-roll of a carousel, which wasn't as photogenic as expected anyway), the "magic hour" exteriors came out surprisingly well, with figures silhouetted against the colorful sky and the light casting a beautiful glow on everything. The next morning I woke up at 5am and headed to Angel's Flight, a location I had intended to use in some fashion ever since the early days back in May. I was pleasantly surprised by this footage as well, especially a shot taken on the promenade overlooking the hill, panning/tilting from a raker below to the just-risen sun peeking out over the city skyline. I turned this into an important transitional shot in the finished film.

It was now December 30, and all the pieces were finally in place. That afternoon I settled in to edit all night long, barely sleeping the following morning and returning from work in the evening to put the finished touches on the first half of the film. Remarkably, this was all wrapped up in time for the first half of

Class of 2002 to premiere on New Year's Eve, the last hours of 2012, which seemed so appropriate in so many ways.

Though I had hoped to turn a new page in 2013, I was obviously still not done with the film. I took a rest for a while, and then plunged back in, incorporating far more video footage in the second half and taking a more stylistically ambitious approach. This was especially true at the film's conclusion. When I reached Jared's passage I realized I did not have enough material to illustrate his story, and so I returned to the trusty Internet Archive to hunt for more stock footage. This time I emphasized Boston and found some great shots, climaxing in a silent assembly of shots from a travelogue documentary of Massachussetts. These were used sparingly for Jared and retroactively added to Rachel's passage (a shot of a horse turning from a fence and walking away from the camera worked perfectly to punctuate a particular moment), by and large reserved for the climactic moment in which Jacob reveals all of his memories and regrets revolving around Leah and the children.

Here, also, music finally came into the picture. I had been struggling with the idea of a score from the get-go, eventually concluding that the best route was to find free classical music online, where many public-domain recordings existed. Yet nothing I found seemed satisfactory. As a result I uploaded the first half without music at all (something I think actually works well there, and wouldn't change). Eventually I discovered a Dvorak symphony I liked, by sampling classical music stored on my iPod and then seeking out another edition on the Internet Archive. Unfortunately, this recording was unsatisfactory in many ways; the passage I wanted to use was too short, and marred by the loud sounds of pages rustling, chairs squeaking, and voices clearing their throats. My solution was to slow it down dramatically and sure enough, the slow-motion version of the music worked perfectly to set the ominous tone of Part 2, and eventually to underscore Jacob's emotional revelations at the film's end. I also used a bit of Bach as he discusses his marriage to Leah.

I uploaded the second half in two parts, back to back, and with that, technically, my work was finished. Yet I wasn't quite satisfied - for one thing, views were very slim (in fact, a day or two after posting, Part 2 hadn't received any views at all). I knew this was never going to be a viral phenomenon, but the complete lack of response was nonetheless disappointing. I decided to upload the film all as one piece (which worked better for the dramatic momentum), and also made various minor technical and aesthetic revisions, as a final last-minute touch adding a logo to beginning and end for "Paradise Pictures" which I suppose from here on will be my one-man studio insignia.

Two days ago, the post went up. Even then my work was not done. Various uploads would not play on my computer screen and I had to create a new YouTube account to post the complete film, since my previous one had been "penalized" for spurious charges stemming from my video essay on

Modern Times in December (more on that at another time...). More late nights, more last-minute revisions, all the way up to now, as the reasonable and productive schedule I envisioned for myself, once this film was completed, keeps getting pushed back.

Even now, writing this piece, which I intended to finish before midnight, it is 4am. I am due at work in 3 hours, so I must be certifiable, but somehow this just seemed necessary. A few stray comments on the video finally fired me up, and made me feel like maybe there's an audience there after all. I hesitated initially to talk about what led to the film, feeling I should let it speak for itself. But like the proverbial tree falling in the woods with no one around, it needed a loudspeaker. Maybe this will help.

So there it is, how it - and I - got here. However, before re-presenting the film itself, I need to address one more topic, the touchiest and most central to the work itself. It was written before what you're reading now, and moved to the end of the piece where it is more effective. So here I can say goodnight and snatch a few hours of sleep, much-needed and hopefully well-earned, before sending you on your way.

Yearbook Dedication: Why the Class of 2002?

Less than a week after the seed was planted for this short film, I struck upon the central concept that would outlast the initial premise and motivate me during dry spells. The five characters, awaiting the last train into the afterlife, would all be the same age. Or rather, they would be different ages but born the same year before dying at various points in the decade since high school graduation. This notion, a kind of macabre class reunion, resonated with me as I approached the tenth anniversary of my own high school graduation and looked back over the years to see mostly dashed dreams, unexpected disappointments, and a slow, hard acceptance of adult reality as opposed to the naive innocence of youth. All generations experience this to a certain extent but the historical circumstances of the Class of 2002 were unique.

Raised in the retrospectively comfortable, confident nineties - when history had supposedly ended - we received a rude awakening on September 11, 2001, which fell right at the start of our senior year. And yet out of this dark moment there seemed to be a greater unity, not just in the nation at large but amongst ourselves. When we graduated that feeling of vague determination and purpose, powered by an unearthed anxiety was still with us. As it turned out, however, it was

too vague, and quickly dissipated by the abrupt and still bewildering turn toward Iraq, the tendency of the cultural consciousness to submerge rather than than address the national trauma, and the eventual economic collapse in which the chickens of avoidance seemed to come home to roost, confronting everyone troubled by but able to ignore wars abroad and looming terror threats at home with a raw, immediate reality that could not be brushed aside.

Meanwhile I noticed that Hollywood, and even independent films by and large, could not capture the zeitgeist. There were some brave attempts, and indeed probably more films directly addressed current events than during the supposedly rabble-rousing Vietnam era. Yet back then, even without confronting the war directly, movies had easily captured the mood of the times in ways indirect yet immediate.

Bonnie and Clyde may have taken place thirty years earlier,

The Graduate may have set a youthful square as its protagonist,

Midnight Cowboy may have avoided Vietnam altogether but for a fleeting moment in which Ratso tells a protesting hippie to "take a bath." Yet they all captured the sixties in ways that few films of my own youth, excepting Spike Lee's magnificently mournful

25th Hour, could claim to capture the zeroes.

Well, I've written about this phenomenon (and my own admiration for

25th Hour) elsewhere, and obviously I couldn't hope to rectify this with a little short film hardly anyone would see. Yet the desire to articulate something I hadn't seen articulated motivated me, even as I knew my film would not openly confront the major events and trends of the decade, except for one character's story and fleeting moments elsewhere. More directly, I hoped to paint a different portrait of the "millennial" generation than that I'd seen depicted in the media, which would have you believe all twentysomethings are perpetual adolescents living in a haze of self-referential irony and irresponsible immaturity.

Never mind that virtually all of my friends are married, many with children. Never mind that many millennials did not go to Iraq or Afghanistan, but that most of the people who did go were millennials. Forget for a moment that unemployment has hit young people the hardest, and not everyone can grapple with it by turning this into an HBO show. When I look back over the past ten years I see a generation forced to grow up much faster than their parents. They are often the ones who have fought the wars - in both sense of the word "fought," shouldering the burden of debt and unemployment, and trying to raise families in an America that seems in many ways to be declining, even as they struggle to reaffirm a hope and idealism that older, bitter generations deny.

I see the film as a tribute to those people, some of whom I count among my friends, even as I recognize that I have often fallen short in my own life. Though we are different in many ways, this is something I share with Jacob - a desire to respect and honor the struggles and often undesired confrontations with reality that life will always toss into our paths, and an acknowledgement that some people have borne this brunt more than others.

The film ends on a bittersweet note which is admittedly quite pessimistic on close examination. It is true to the character, and while it was tempting to end the film with a serene shot of the sea (inspired by the closing sequence of

Contempt), suggesting that an eternal order outlasts the trials and travails of human suffering, I chose instead to tilt down to the tunnel below. There the film ends, a descent to complement the ascension with which it opens.

I do acknowledge the existence of transcendence but right now, in this film, it feels necessary to emphasize the opposite quality. Raised in hope and confidence, however tinged by fear and a latent uncertainty, it is the disappointment that appears the more shocking, and the more character-defining, for the Class of 2002...in this film, and elsewhere.

Class of 2002, the film

Well, from here it's up to you. If you like the film, please share it with others, however possible. It is your word of mouth, or the virtual equivalent thereof, that will bring further viewers my way. Thanks for reading - and watching. See you next time.